The American intellect owes its striking characteristics to the frontier. The coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and evil, and with all that buoyancy and exuberance which comes from freedom – these are the traits of the frontier. – Frederick Jackson Turner |

This all too brief memoir (largely hand-crafted by Dr. Albert M. Wigglesworth in 1958, in his 86th year) is dedicated by his children with great admiration and affection to his and his devoted spouse’s loving memory and lingering influence; and to their children’s children – ad infinitum – as a prideful reminder of an authentic frontier heritage and as an enduring source of inspiration. |

CONTENTS

PICTURES

Waterfall Ranch (Falls in background)

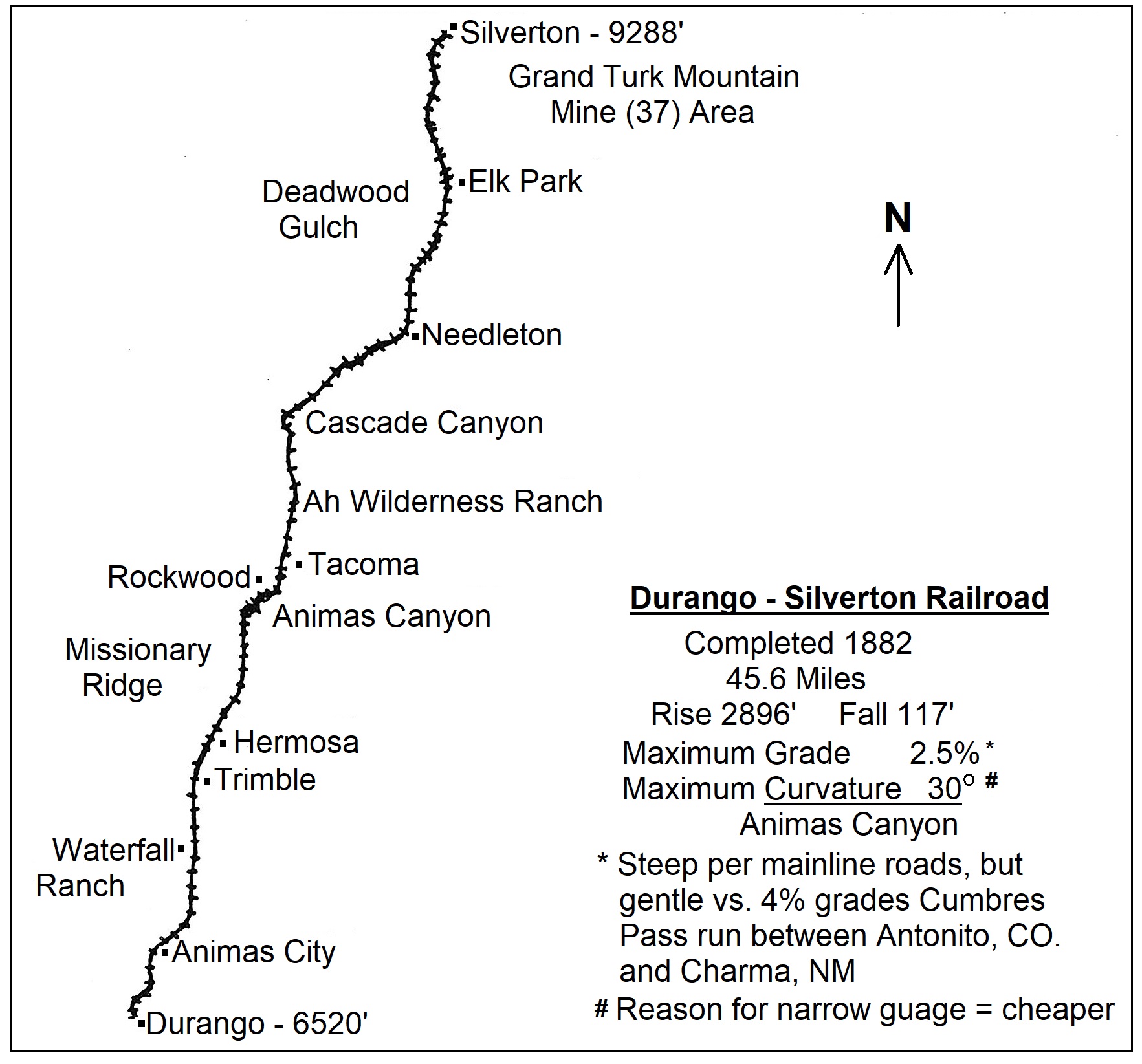

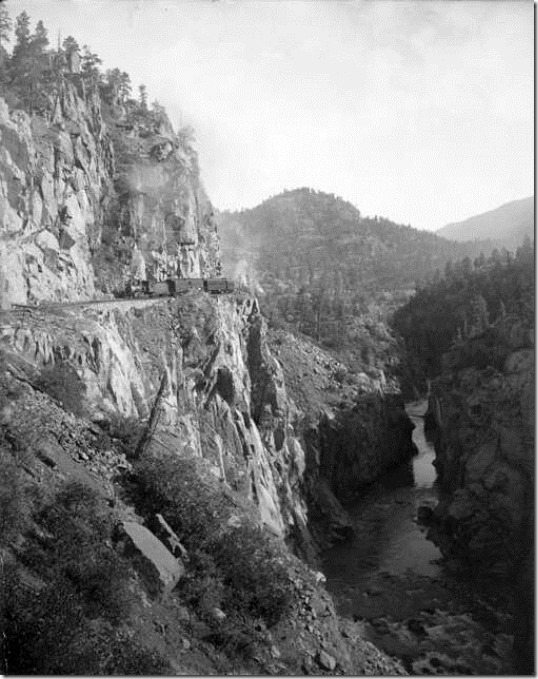

The Durango–Silverton Railroad

Navajo Medicine Man – Hatathli

This document is a reproduction of a manuscript originally produced digitally by Jack Wright in 1986 from the hand-written notes of its title character, Dr. Albert M. Wigglesworth. It was re-created from a printed copy of Jack’s product by his son Charles Wright in the summer of 2021, as a way of making it more accessible to future generations.

The question arises: If this is the story of the Wigglesworth clan, then who is Jack Wright? The answer, only vaguely implied in Jack’s Forward with additional ‘clues’ sprinkled elsewhere in the story, is that Jack is a nephew of the book’s title character. While that genealogical description correctly describes Jack’s relationship to Al Wigglesworth, it provides little insight to those readers who, like this editor, might describes themselves as “relatively illiterate” – that is, someone for whom Mothers, Fathers, Grandmothers, Grandfathers, Aunts, Uncles, and Cousins of multiple generations, spread across a large family tend to blur into a single indistinguishable crowd of relatives. Moreover, it doesn’t identify very precisely where Jack fits into the family tree. For clarity then, this editor adds here a brief genealogical explanation:

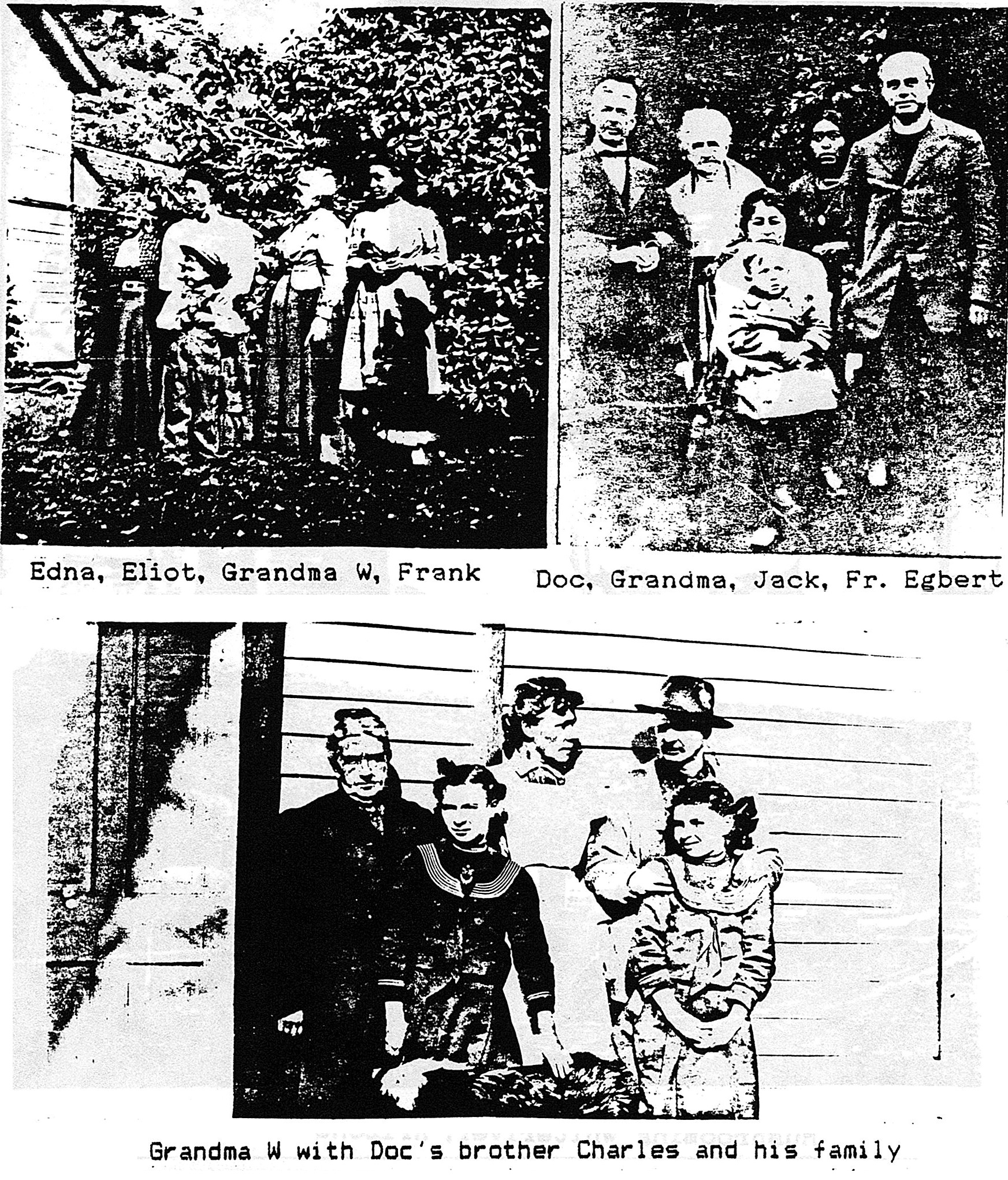

As you will read in the FOREWORD to follow, Al Wigglesworth married Edna Mae Wright. For reference, Jack provides a graphical representation of the Wright family tree in the Family Trees figure at the end of Chapter I – ORIGINS which depicts Edna Mae as the child of J. E. Wright and Susannah Watson. The only child depicted in that figure, she was one of eight siblings comprising two boys and six girls. Her younger brother Herbert F. Wright (himself mentioned several times (see page 199, among others) was Jack’s father, making Edna one of Jack’s Aunts. Thus the title character of this book, Al, becomes one of Jack’s uncles.

As it happened, in 1986, one of Al’s sons (yet another Jack, to whom you will be introduced in due course) suggested that Jack Wright create a context for the memoir that would give some perspective on the Doctor’s life and the contribution he made to the Navajos and to medicine. Realizing that the Doctor’s father, the 19th Century railroad construction engineer, Thomas Hudson Wigglesworth, was also worthy of note, Jack presented an in-depth review of Thomas’ story as well.

This editor’s goal was to simply re-create, as closely as possible, Jack Wright’s original product. Sadly, the original manuscript, with several of Jack’s hand-drawn illustrations, and including numerous family photographs, has been lost. Surviving copies are all the product of copy machines and, after multiple generations of copying, picture quality has suffered greatly. In order to best re-create the original, this editor recreated most of Jack’s hand-drawn illustrations to improve their legibility. Pictures of a general nature have been replaced entirely with similar pictures. Family pictures, however, were not available.

Imagine this editor’s surprise, then, when an Internet search yielded a downloadable version of an edited (and much-expanded) version of Jack’s manuscript posted by Dennis Jensen (see http://dennisjensen.us/WIGG/wigg.htm.) Dennis, it turns out, is the brother-in-law of Ann Barbieri – daughter of Jack M. Wigglesworth (who, as noted, suggested that Jack Wright create this manuscript) and the eldest grandchild of Dr. Wigglesworth. In Dennis’ edited version, you will find most of Jack’s original manuscript, plus significant additions, including comments from many of Dr. Wigglesworth’s children and grandchildren which add tremendous detail to this already engrossing story. The expanded version of this saga posted by Mr. Jensen also contains a large number of additional photos and, perhaps more importantly, extensive list of references to original source material which will well-serve anyone wishing to delve more deeply into the stories presented here.

Returning to this editor’s goal of re-creating Jack’s work, Mr. Jensen’s creation was set aside and work was begun on transforming the printed copy of Jack’s book into this digital edition. The text was recovered by scanning the Jack’s printed manuscript and then converting it to digital text using the Optical Character Recognition software provided by www.pdf2go.com. The resulting text was then painstakingly reviewed to correct conversion errors and formatted to look as much like the original manuscript as possible. Some pictures included herein were extracted (with permission from Ann Barbieri) from Mr. Jensen’s version. Other original pictures could not be located, and are retained in this edition as copied directly from Jack’s work.

This editor assumes responsibility for any and all spelling and formatting errors found in this version but takes no responsibility for the often painful attempts at humor that Jack frequently inserts, or for the sometimes inappropriate cultural references which, though they reflected the popular culture of the 1980’s, have since come to be seen unseemly as or even racist. Such remarks are retained simply because they accurately reflect the original writing.

Numerous footnotes (and a few additional photos) were added where this editor felt they would add useful detail. It is presumed that Jack would have added such footnotes had the software tools available to him when he produced the original manuscript provided the capability to do so.

This editor hopes you will enjoy reading this as much as he enjoyed editing it.

Charles Wright

September 2021

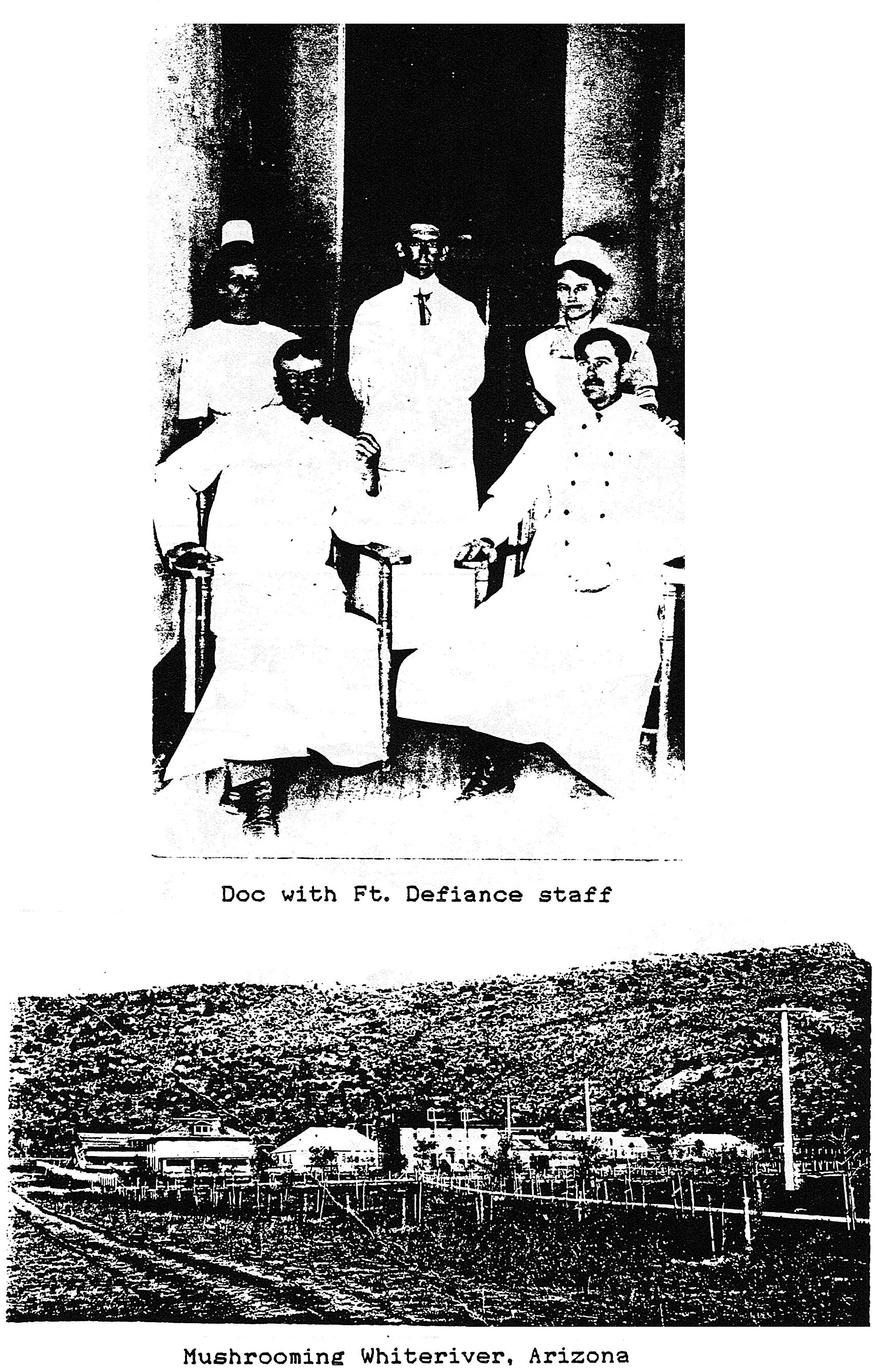

This Memoir has been compiled mainly from a hand–written manuscript crafted by 89 year-old Dr. Albert M. Wigglesworth at Carroll Manor in 1961, just three years before his death. The MS1 essentially covered doctor’s early years and education, and then focused on his quarter-century medical service to the Navajo and Apache Indians in the southwest USA from 1900 to 1925, when he was also raising family comprising three young men. This was clearly the happiest and most fruitful period of Dr. Wigglesworth’s life, which really continued until the death of his beloved wife, the former Edna Mae Wright, in 1954.

To round out the story of their life together resort has been had to other sources, especially. the archives of their two surviving sons, Frank and Jack Wigglesworth. Every reasonable effort has been made to credit published sources, which include but are not limited to the following: The First Americans, Time-Life Books, NYC; Here Come the Navajos – Bureau of Indian Affairs; 1918-1920-1922 Annuals – Franciscan Fathers of St. Michael's Mission, AZ; Padres’ Trail – Franciscan Fathers; Carrollette – O. Carm.; Trek Along the Navajo Trail – Trek, Inc., Durango, CO; Rio Grande Green Light, 15 Jul 1947 – RG RR; Sagebrush Metropolis, Durango 1880-1881 – Durango Herald, 1977; Durango Herald Democrat – 30 May 1948; the Silverton Standard & the Miner – 8 Jul 1982, 26 Aug 1982, 1982 Visitors Guide; Cinders and Smoke – Western Guideways, Lakewood, CO; Fort Defiance and the Navajos, Pruett Publishing Co, Boulder, CO; and the Smithsonian, Jul 1986. Both scenic pictures and text have been drawn from these sources. The Wigglesworth family provided the more personal pictures.

Fortified with the foregoing material, compilation of this 50,000 word Memoir was accomplished May-Sep 1986. It is sincerely hoped that family members will find the tale as interesting and inspiring as the interlocutor did in its preparation.

Jack Wright

14 Sep 1986

Every man is a quotation from all his ancestors – Ralph Waldo Emmerson

WASHINGTON STAR, 16 May 1946: About the liveliest person in Washington today is a Indian chief, Chee Dodge, He’s in town with a delegation of Navajo braves, trying to convince Congress it should ante more cash for the education of his tribe. Chief Dodge has been to the Interior Department and to the House and the Senate to explain that there are 20,000 Navajo children, but only schoolrooms enough for 6,000.

He went before the House Indian Affairs Committee yesterday to speak his piece, in Navajo. The translation was supplied by his son, Tom, who wore a tan sports coat, neatly matching tie and pocket handkerchief, and looks like the successful lawyer he is.

When he felt a point needed amplification, the aged chief would leap to his feet, shake his magnificent head of white hair, wiggle a dramatic finger, then turn -loose a torrent of Navajo. And a torrent of Navajo can leave the verbose member of Congress at a loss for words.

It turned out the old boy had a sense of humor, too. Once, without waiting for a translation, he came up with a reply in perfect English. He then explained to the astonished committee that he spoke Navajo only because many of the 22 delegates with him knew no English. “Actually I had a tremendous education for my day,” he assured the committee. “l went to school for two months.”

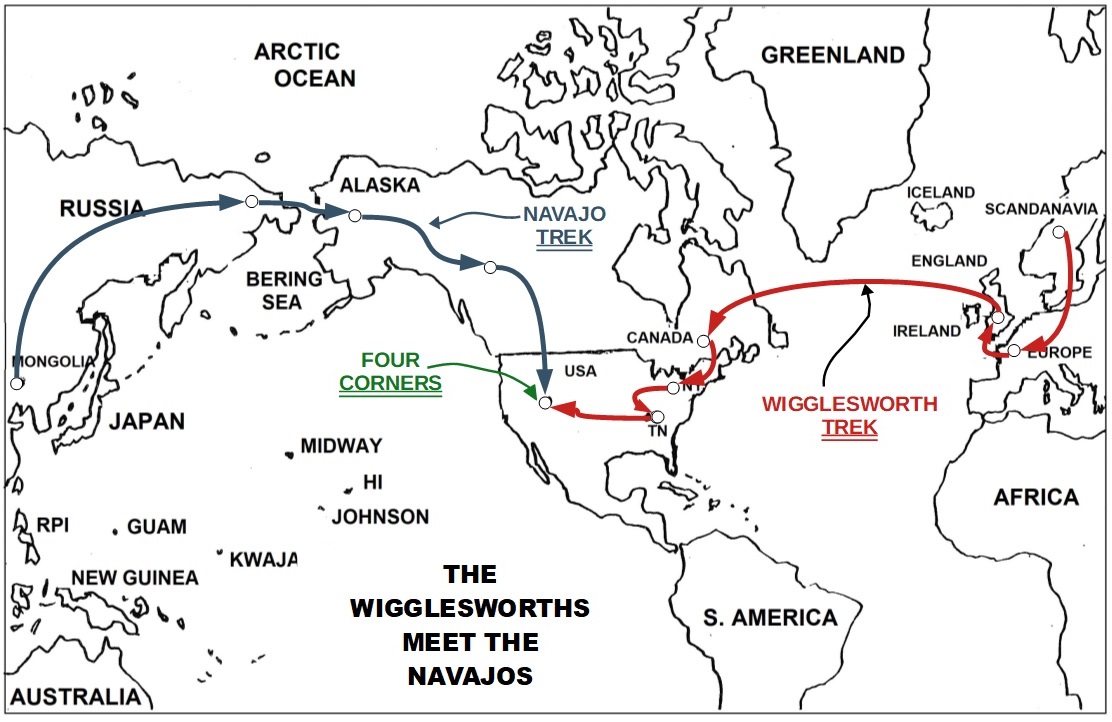

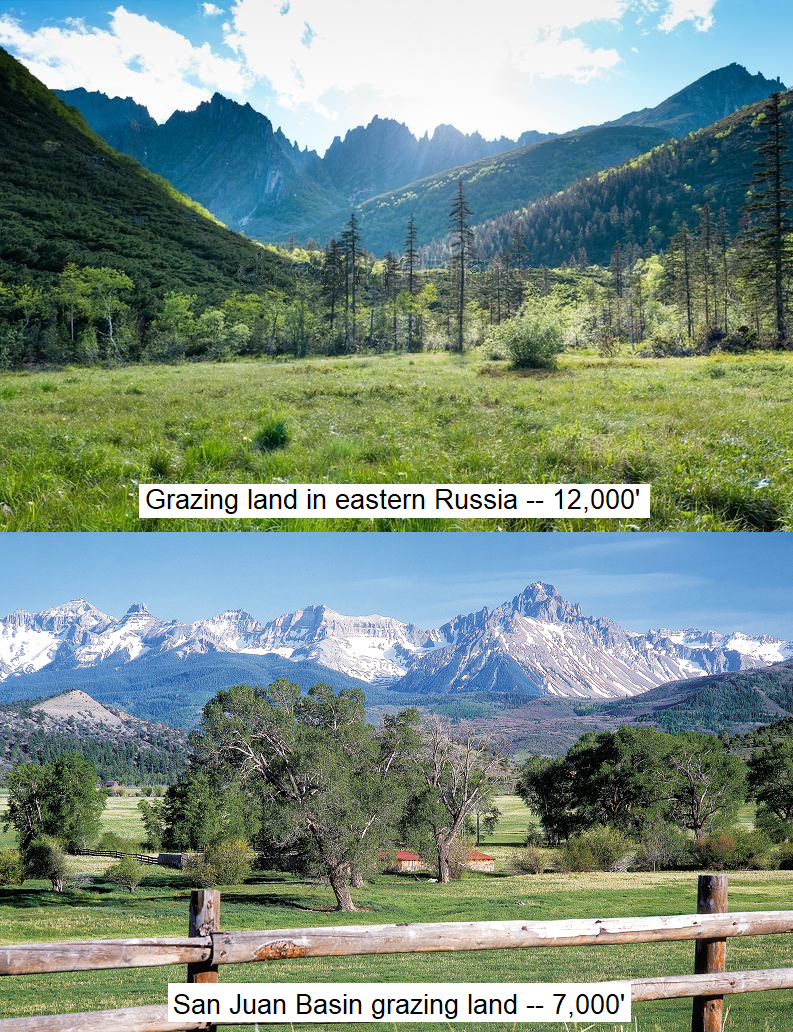

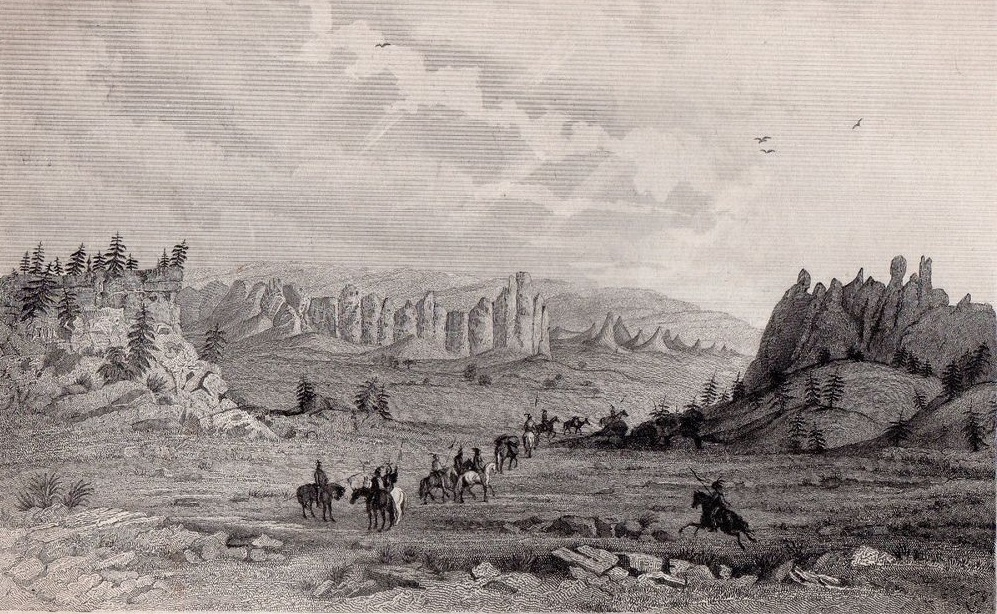

This is the story of Dr. Albert Matthew Wigglesworth. It is therefore also necessarily the story of the plight of the American Indian, especially the Navajo of the desert and mountain area broaching the northern ends of New Mexico and Arizona and the southern ends of Colorado and Utah. This would be the Mesa Verde and San Juan Basin areas roughly centered on the four-cornered conjunction of the aforementioned states – the only place in the United States where four states meet, and accordingly reputed to be the most photographed spot in the entire country.

The near half-century merger (1878-1925) of the Navajo Indians and the Wigglesworth clan around and south of the Four Corners area of the Mesa Verde-San Juan Basin region of the southwest USA shall be the central focus of our story. Here, these two “tribes” for all time put to rest the ‘Kipling contention that “East is East, and West is West, and never (Barbara Walters2-wise) the twain shall meet,” because, we may now say, it was precisely through the train that they did meet (about which more later). Actually, the two parties, both of which originated in the far north long ago, approached the area from opposite directions, with the Indians arriving first by perhaps a bare 25,000 years!

Navajo legends contend that their people (dineh – pronounced “din NAY”) emerged from “the underground” into the southwest USA. Don’t you believe it! Rather, it seems that the North American advent of the Indian was more or less a geological “accident” of ice-age mechanics. The essential by-product of these frigid forays was a land bridge called Beringia3 which long ago joined Siberia and Alaska. This was a lush land-link nurtured by the natural fertilizers of sea animals and plant remains. The verdant foliage lured “big game” animals from Asia, and then their hunters.

It is generally believed that this bridge was further augmented by a glacier-free corridor (estimated as no more than 25 miles wide) through northern Canada only between 20,000 to 28,000 and 32,000 to 26,000 BC4; a wall of ice as much as a mile high otherwise stretching from the Atlantic to Pacific and blocking all access south. It is generally held on the basis of artifacts scattered through the Americas that the Indians arrived about 30,000 AD! More specifically, Indians are placed at Mesa Verde, CO, by 1100 AD – which still represents quite a jump on the Wigglesworths. The initial occupants of the Four Corners area (who peaked about 1200 AD) are figured to be the so-called Anasazi, that being the Navajo word for “the Old Ones.” The era of big game is said to have prevailed from about 9000 BC, followed by a period of foraging from about 4000 BC, followed by the advent of farming around 1000 BC. Some farmers began forming villages around 300 BC. It was not until about 900 AD that the Anasazi started building pueblos, that being the Spanish word for “village.” (One of the most famous pueblos is the Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace located in an enormous cave and containing more than 200 rooms capable of accommodating several hundred people.) Eventually, with the introduction of sheep (and horses) by the Spanish in the 14th century AD, the Navajo (“Successors,” with the Apache, of the Anasazi) became an essentially pastoral people, but also renowned for their artistry with turquoise-ornamented silver jewelry and the weaving of baskets, blankets and shawls.

One interesting sidelight of the latter two crafts is the frequent adornment of their products with the design known as the swastika. Most people born since the 1930’s will most likely recall it with repugnance as the symbol of arrogant racial superiority flouted by Hitler’s Nazis. That’s really too bad, because the symbol has a more noble connotation as reported in the 1972 Annual of The Franciscan Missions of the Southwest. The Ae’Nishodi Biae Danaezigi, or Men Whose Robes Drag in The Dust – or more simply Long Robes, report therein that extensive research reveals the swastika in fact to be a fitting symbol of “the ethnic unity of the human race” – in virtue of its prehistoric origin and almost universal use. It is to this day the principal ornament with which some Indians deck themselves for the performance of their religious ceremonies.

Ruth Underhill’s Here Come The Navajos suggests that, “The key to the Navajos comes through their language.” With the exception of the related Apache, it is unlike that of any other Indian tribe. “Navajo sounds and Navajo grammar are entirely different,” according to Dr. Underhill. They have no f, p, q, r, v, or x – although all are used for renderings in English, and consonants predominate. War buffs will recall that, precisely because of the uniqueness of their native language, Navajos were pressed into service as telephone and radio communicators in the front lines during WWII. The Army first stumbled on this bonanza in WWI. It was a unique service providable only by our American Indians. Most of their languages had never even been written down, and Navajo was further complicated in that translation was never word-for-word. (For example, “Hitler” was automatically transposed to Mustache Smeller, and Mussolini to Big Gourd Chin, while Doc would become Medicine Man With Limp and son Frank would be known as Turkey Egg because of his many freckles. Incidentally, the Wiggs5 treasure copy # 153 of a 325 copy edition of a two volume Vocabulary of the Navajo Language produced by the Franciscans at St. Michael's, AZ, in 1912.) The Navajo code-talkers operated from Italy to New Guinea in the South Pacific. Some 375 of them had been recruited into the MarCorps by the end of WWII. The Navajo language is traceable to tribes inhabiting northern British Columbia and Alberta, the two westernmost Canadian provinces bordering the USA. The language is called Athapascan (variously “Athabascan” – there being as many spelling versions of Navajo words as of the name Gaddafi6, rhymes with daffy,) due to its orientation around Lake Athapasca – Lake of the Reeds, or (in Navajo) there is scattered grass.

Another interesting sidelight of the language is the nature of Navajo names, (For religiously inclined readers, the Navajo rendering of “Jesus Christ” is Doodaa-Tsaahi, which is not to be confused with Zippity-Doo-Dah or Doo-Dah-Day. Knowing this, one still should go to church on Sunday.) The name “Navajo,” incidentally, means great planted fields. It might more appropriately have meant “adaptability,” since that is what characterizes the Navajo in great measure. They readily undertook to learn a whole new way of life as farmers and herdsmen, whereas the more nomadic Apache stuck largely to foraging and was a generally nasty neighbor. In fact, Apache is the Zuni word for “enemy,” and Geronimo (1829-1909) was still warring against the US (not without cause) as late as 1885-86 (although he eventually became a Christian and marched in Teddy Roosevelt’s 1904 inaugural parade). Nor was the wily and courageous Cochise (1815-1874) often mistaken for a really nice guy – especially after 1861 when soldiers unjustly hung several of his relatives. (Even Edgar Rice Burroughs of Tarzan fame was moved to write two 1927 novels focused on Geronimo or Goy-ath-lay – the Man Who Yawns. At one point, he has the wise old chief say, “Some day the Nalgai Lagai (white eyes) will keep the words of the treaties they have made with the Inizhini (Indians) – the treaties they have always been the first to break.” Well, one can hope.)

The Navajo used no surnames, but had both “private” and public personal names. And, like most other Indians, they did not call each other by the highly poetical names common to novels and old movies, such as Fleet Antelope, Running Bear, or Soaring Eagle. (Once again, this paraphrase is all courtesy of the Long Robes.) On the other hand, one frequently met such prosy names as The Liar’s Son, Frozen Feet, Mister Mud, Little Horse Thief, Squint Eye, or Club Foot. For this reason Navajo were never addressed by the name under which known. It would be an offense against decorum and usually not at all flattering. Hence their bashfulness, too, when asked their name. They’d hedge by saying Holla; the equivalent of the Spanish Quien sabe for “I don’t know.”

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, to learn that most Navajos assumed a second or “public” name which they used in normal commerce. This practice was virtually forced upon them by book-keeping incident to their wanting to be paid. Needless to say, these self-chosen names were more complimentary, as for example, the equivalent of Mr. Tall Man – Qastqin Naez. It should go without saying that English translations are generally inaccurate. Thus, Black Horse is not a proper translation of Bili Lizhini which literally means “He whose horse is black.” Little wonder, then, that the Navajo were generally addressed by the more generic Qastqin, which is “Mister,” the equivalent of Senor in Spanish. It only remains to remark that The Lone Ranger did his faithful Indian companion no honor by calling him Tonto, which is Spanish for “Crazy.”

Perhaps the most remarkable thing is that shortly before 1300 AD this way of life came to an abrupt and mysterious end in much of the southwest. Why it did is a mystery even today, but the most likely explanation seems to be the abundant evidence of a severe drought that apparently gripped the region toward the end of the 13th century. This would not, of course, explain the failure of the Pueblo to return to their monumental villages. It seems most likely that they discovered that their lands had in the interim been taken over by more war-like tribes. Thus, it is generally concluded that the Athapascan predecessors of the Apache and Navajo infiltrated the area through the 12th to 15th century AD. These folk were skillful warriors with a new weapon, borrowed from the Eskimo – a bow backed and strengthened by springy sinew which made them the fastest, hardest, straightest shooters in the west – as the Spanish, Mexican and United States’ governments were to discover in turn. It is said that even today Zuni mothers frighten naughty children by telling them that the Apache will come and get them. (The bulk of this early Indian lore is derived from TIME-LIFE’s The First Americans.)

Continuing our historical stage-setting, the Spanish incursion, principally along the Rio Grande valley, generally transpired between 1540 and 1821. The Spanish explorer Coronado swept up from Sonora, Mexico, opening up the American southwest in 1540-42, searching for the fabled seven cities of Cibola. Legendary for their gold (El Dorado,) they are believed to have been in the general area of the Zuni country around Santa Fe and, in fact, Zuni, NM, is the only one of the “gold-less” seven cities that survives. (One group split off from Coronado’s party to the west and discovered the Grand Canyon.) As recently as 30 Jun 1986 the Washington Post reported the possible finding of one of Coronado’s 16th century camps – the first non-Indian campsite found in New Mexico – revealing seven iron horseshoe nails, a sewing needle, a piece of metal horse harness, and burnt beans and corn kernels, together with fragments of pottery of a type made and used by the Spanish in the 1500’s. The Indians at that time had neither horses nor iron. Note that Coronado’s settlements preceded the more familiar colonization of our east coast!

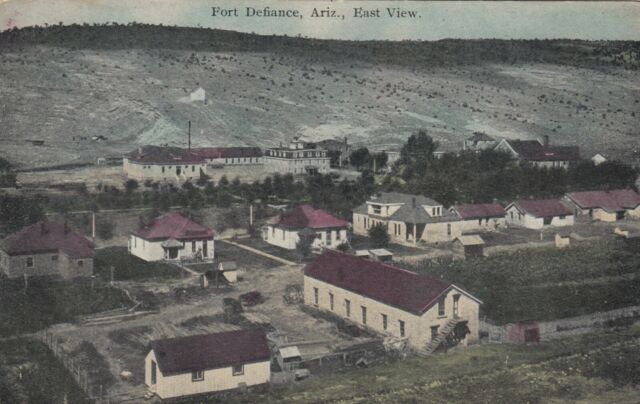

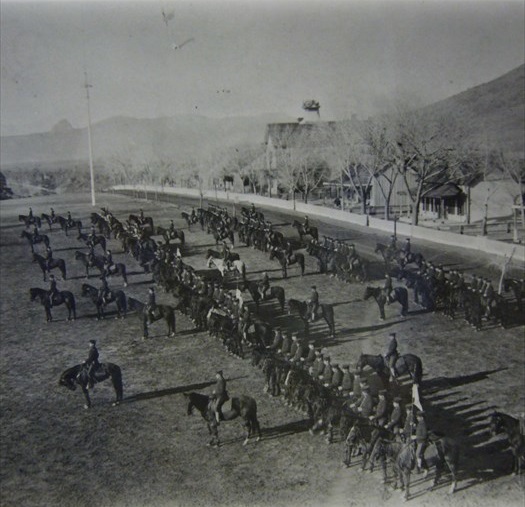

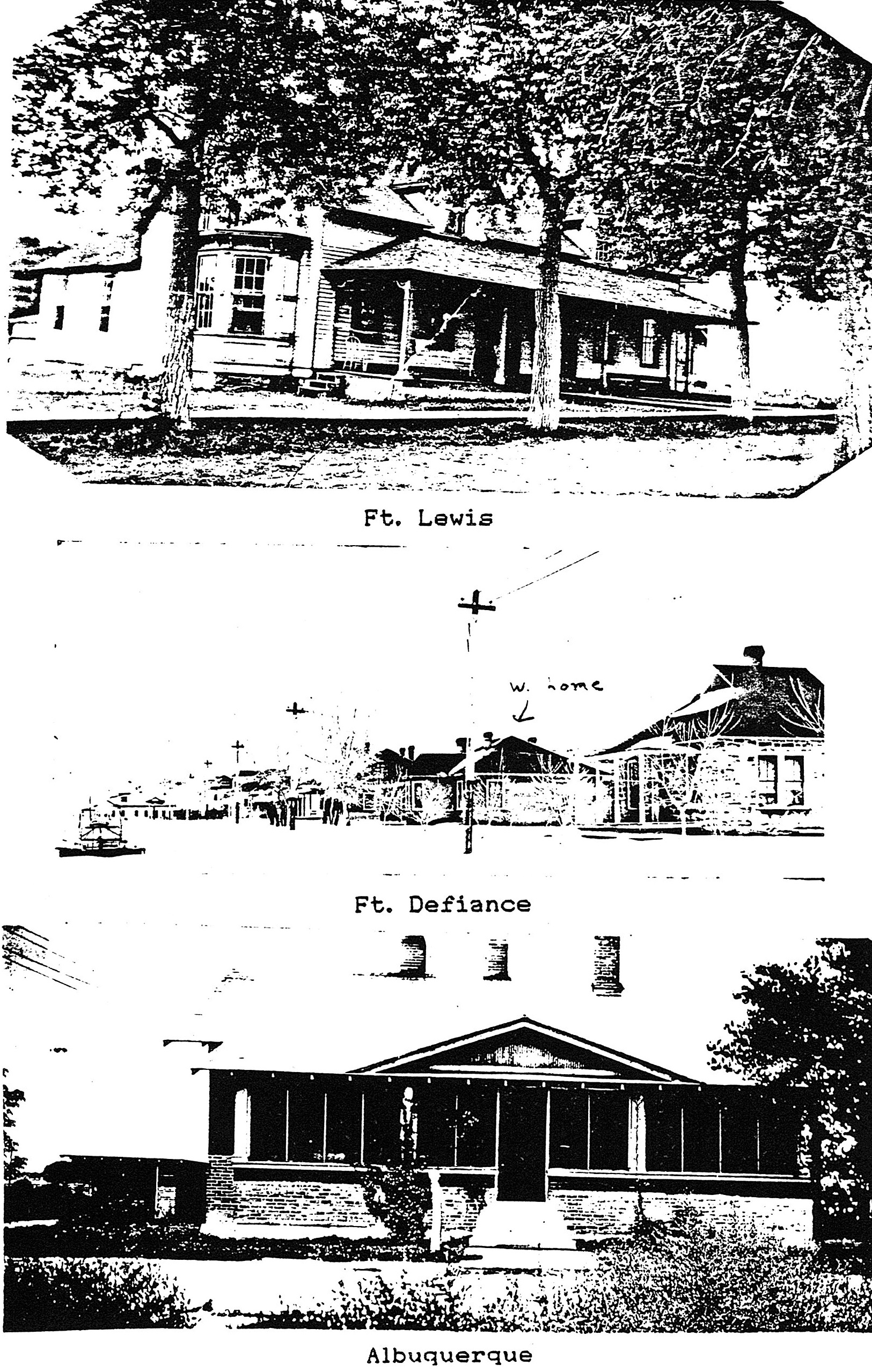

Following its independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico became monarch of the southwest until the invasion of U.S. troops in 1846. The treaty of Guadaloupe Hidalgo ceded the area to the U.S. on 2 Feb 1948. Neither Spain nor Mexico ever succeeded in subjugating the Navajo. It would take the U.S. 17 years (although front-page 7 Jul 1986 newspaper headlines suggest that in their land dispute with the Hopi and the U.S. government the Navajo may not be fully subdued even yet). The first foray by the U.S. against the Navajo was concluded at what would become Ft. Wingate in a peace treaty on 22 Nov 1846. During the next 15 years six other treaties would be drawn up, agreed to, and signed: at Beautiful Mountain (20 May 1848), at Chinle (9 Sep 1849), at Pueblo of Jemez (HAY-mess, 15 Nov 1851), at Laguna Negra – just north of Ft. Defiance – (18 Jul 1855), and at the eventual Ft. Wingate (25 Dec 1858 and 18 Feb 1861). Only the first (1848) treaty was ever ratified by the U.S. Senate. Also, during this period the first military post in Navajo country was established at Ft. Defiance on 18 Sep 1851. The latter would be the birthplace of all four of our hero’s children.

It should go without saying that these treaties were mostly honored in the breach by both sides, although the U.S. managed the best PR, and generally succeeded in placing the onus on the hapless Navajo as war alternated with peace into the spring of 1863. At this point the U.S. determined upon an all-out war to subdue the Indians once and for all. Col. Kit Carson was chosen to spearhead this effort. He succeeded with a Sherman-like “scorched-earth” campaign that wiped out the Navajo shepherds and other livestock, devastated their cornfields and orchards, burned their hogans, and generally lay waste to their country and destroyed their economy. The Navajo were virtually starved into submission. Eventually, half of the tribe (some 8,000) yielded to the 400 mile Long Walk from Ft. Wingate (near Gallup) to internment on a 21 acre plot at Ft. Sumner on the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico, where they were to remain for the next four years as President Lincoln proclaimed it a Reservation. (In 1881 Billy the Kid fared less well, being put to rest there permanently by a bullet from Sheriff Pat Garrett.)

Conditions at Ft. Sumner were euphemistically described as “far from ideal,” which hardly conveyed the notion of Comanche raids, crop failure, insect infestation, bad water, the depletion of wood for heating and cooking, and the rampant sickness and disease that prevailed there. Little wonder that by the end of four years the Navajo were making ardent overtures for a return to their homeland. This was met by the U.S. dispatching no less than General Sherman himself (of the devastating “Atlanta march to the sea” fame) as negotiator. Offered a choice of being sent to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma – of ultimate “Cherokee oil7” fame – the Navajo opted overwhelmingly to return to their homeland in a final treaty formalized on 1 Jun 1868. Their trek began two weeks later, in the company of their first Indian Agent, Theodore Dobbs. Soon after, Ft. Defiance was designated the-first Agency Headquarters. Dr. Wigglesworth would make the scene in Dec 1904, One might be forgiven for conjecturing that his contribution to their improved health played a significant part in the Navajo being the largest tribe in the U.S today, numbering about 160,000 in 1980.

So, now, whence the Wigglesworths to Ft. Defiance and their tryst with the Navajo anyhow? Well, they were initially rooted in the far frigid north also, but in the Scandinavian rather than Siberian area. Our European brothers, of course, only reached our shores via the Atlantic in the 15th century, and thereupon set about with a vengeance to eradicate the Indian culture they encountered much to their surprise. They did a pretty good job of it, too, but our hero was not a party to it – about which much more later. If, before moving on, we might pause a moment to conjecture a hypothetical conversation overheard by an Indian between, say, Leif Ericson and Columbus as to whom was the true discoverer of America, we might well expect him (or her – equal time!) to explode, “Discover? Hell! We knew it was here all the time!”

Nevertheless, the Wiggs clan came a long, long way. It all began when the Norsemen from Scandinavia invaded the Franks in the 10th century. (Vikings is a more generic term for these fearless adventurers, and includes those bound for the New as well as the Old World.) The Franks were a Germanic tribe that settled along the Rhine in the 3rd century. Under our old high school history acquaintance, Clovis I, they moved into Gaul (the land roughly west of the Rhine and north of the Pyrenees, and which is perhaps best remembered by novice Latin students as being “divided into three parts8”). In. any event, the kingdom of the western Franks became France in 870. (Yes! There will be a quiz!) With the coming of the Norsemen the northwestern corner of France eventually became known, as it is even today, as Normandy (just “think” D-Day). This seems as good a time as any to remark that the Anglo-Saxons were yet another Germanic tribe originally situated at the mouth of the Elbe (look it up9) who conquered England in the 5th to 6th centuries. Now you understand why English bears such a close phonetic relationship to German.

Anyhow, beginning about 841 the Norsemen regularly penetrated and plundered as far as 75 miles up the Seine to Rouen, and even on to Paris. Their occupation was finally formally sealed by the treaty of St. Clair-sur-Epte in 911 which established Rouen as the capital of Normandy, and the Norsemen leader, Rollo, as the first Duke of Normandy. (Rouen may be even better remembered as the site of Joan of Arc’s flaming farewell in 1431 – certainly it was by Joan). Rollo prevailed until 931, to be succeeded by the second Duke of Normandy, William Longsword.

There now followed a series of Dukes: III – Robert the Fearless (942), IV – Robert the Good (996), V – Robert the Devil (1027), and VI – William (1035). The latter really changed things, putting down a rebellion of nobles in 1047, and culminating a Norman penetration of England in 1050 at the battle of Hastings (14 Oct 1046) in which he, as William the Conqueror, overwhelmed the English (killing King Harold II, the successor to Edward the Confessor – of five pound crown10 fame). He was Crowned King William I on 25 Dec 1064. This was at about the same time that a comet, to be known as Halley’s, put in its first recorded appearance.

Now the scene shifts somewhat and the plot thickens. So, where are we? In England, at last, or, to wax poetic: Oh, to be in England, now that April’s there… (Credit Robert Browning.) But wait, we must back-track a bit. It seems that about 950 AD there lived in Normandy (near Rouen) a man named Herfast, but known as the Forester of Equipqueville. He had five very beautiful daughters. He is thus described as the Lucky Forester, since these nubile Normans all married prominent knights from whom descended most of the nobility of Normandy, which later became the nobility of England. (You don’t have to take our word for it, see Freman’s History of the Norman Invasion.) The first daughter became the spouse of the Earl of Hereford, the second of Earl of Warwick, and the third of the sire of the Earl of Buckingham. The fourth daughter wed the third Duke of Normandy, whose grandson was to be William the Conqueror. Finally, the fifth sister married Godfrey, brother of Osbern de Bolbec, and if you’ll just be patient, we’ll next recount how the Wigglesworth clan evolved in due course from this latter stem. We first wanted to establish (through the relations – if you’ll pardon that expression – of the fourth and fifth sisters) how the Wiggs can claim a lineage back through William the Conqueror.

Well, the fifth sister and Godfrey had a son, William, Vicompte de Arques (III). He had two sons, William (IV) and Osbern (IV), both of whom survived the battle of Hastings (1066) and are to be found in the Domesday book of English land-owners with substantial holdings in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire in northeast England. Guess what? Osbern (IV) had two sons, William (V) and Osbern (V), and the former had a son, William (VI). Good grief, Lucy11! With both of the only two male names this branch apparently knew now already used, what was poor William (IV) to name his male progeny? Mysteriously, it is precisely at this point that this line disappears from the records without a trace. Meanwhile, retribution was swift for Osbern (IV), since his grandson, William (VI), had no male off-spring and this line too became extinct. Now, it was all up to William (V), and he managed both a son and a new name – Peter (VI), who came through handsomely by spawning four sons. Well, suffice it to say that the line continues to William (IX,) who partially anglicized his name from William de Arques to William de Arches. Now, it happened that this William (and perhaps his father) owned the ancient property and town of Wykelsworth, which derived its name from the old Saxon name of Wykel, and Weorth, the old English for farm or estate, and thus came down through the years as Wykelsworth.

Now, it also happened that at about that time there were three or possibly four William de Arches living in this part of Yorkshire. It is not surprising, therefore, that our William chose to distinguish himself by appending de Wykelsworth to his name. There may also have been a further reason for the name change. Along about 1189 his father’s uncle, Gilbert, had rebelled against the king, and was captured and his property confiscated. This disgrace may also have impelled our man to disassociate himself from the de Arches. In any event, the Wykelsworth fortunes prospered, and the clan for generations occupied Wykelsworth Manor, comprising some 4500 acres (about 7 miles square). By the 16th century the family name was variously spelled Wykelsworth, Wigglesworth, Wiglesworth, and even Wrigglesworth, but life went on. It went on, in fact, all the way to Palmyra, New York, where emigrant Matthew Wigglesworth died in 1873.

We shall pursue the thread of this family story in the next chapter. Meanwhile, a few observations seem pertinent. First, a word about the Domesday (pronounced doomsday) Book – evidence supreme of the extraordinary 900 year continuity of the British government. It is a comprehensive land register and demographic survey commissioned by William the Conqueror 20 years after the Battle of Hastings – which evolves landholder-by-landholder and almost field-by-field. The name derives from the book being so formidable as purportedly to suffice as a record for doomsday itself. It is currently being converted to computers, which has been likened to straightening up the leaning Tower of Pisa, even as describing the book as a survey has been likened to saying the pyramids are graves.

Second, following the evolving and ultimately merging histories of both the Navajo and the Wigglesworths, one can’t help but be struck by the recurring theme of their violent struggle for survival as wars succeeded wars. That’s the bad news. Lastly, there is the good news: one is also impressed by a gradual but steady transformation toward civility. It should be a matter of no small comfort in these trying times, haunted by the memory of two World Wars and ever-threatened by potential nuclear disaster, that mankind is improving. In a sense, that is what this story is all about. The Wigglesworths, personified by a compassionate Dr. Albert M. Wigglesworth, confronted the Navajo in the Four Corners area of the southwest United States, and the ministrations of the good doctor will do much to mitigate the Indians’ anti-white instincts as nourished by the deplorable injustices inflicted by earlier white pioneers and their government. Our story, then, is that of the pilgrimage of mankind in microcosm.

We’re all omnibuses in which our ancestors ride. – Oliver Wendell Holmes

Nearly every American adult remembers the Bear, the late great Alabama football Coach, Paul “Bear” Bryant. Most “senior” sports fans recall the two Baers; Max, who won the World Heavyweight Boxing Championship by KO’ing Primo Carnera in 1934: and younger brother Buddy, who was one of Joe Louis’ Bum of the Month victims in 194114. And surely everybody has heard of the three bears made famous by that prototype hard-to-please vixen, Goldilocks. But, what about four bears? How many people really know very much about their forebears? (Sorry about that, folks!) The question had to be asked in a palatable manner, and we shall now attempt to answer it for the Wigglesworth clan as descended from our protagonist, Dr. Albert Matthew Wigglesworth, hereinafter affectionately referred to as “Al.”

We have already traced the Wigglesworth strand of Al’s ancestry from Scandinavia, via France and England, to New York state at some considerable length. It is only fair, then, that we interrupt that story at this point to inject some background concerning the strand that produced Al’s wife. Family tradition has it that the Wright clan, which spawned Al’s devoted wife, Edna Mae Wright (whom we shall meet shortly), traces it’s ancestry as far back as William Penn. Unfortunately, no documentation on this point comes readily to hand. We can, however, be a little more definitive regarding this branch of the family from about the same time (the late 18th century) that we find the Wigglesworth clan established in the United States in Palmyra, New York. Specifically, the maternal line of Edna’s family is traceable to the marriage of Elizabeth Green and a W. W. Dorney, both of Harford County, Maryland, by the first American Catholic hierarch and founder of Georgetown University, Archbishop John Carroll, on 11 Sep 1796. The amazing aspect of this branch of the Wiggs family tree, on both the paternal and maternal sides, is that it was DC-Maryland centered for generations.

Now, the Dorneys had a daughter, Maria Agnes, who married Benjamin Thomas Watson of Prince Georges County, Maryland. They, in turn, had a daughter, Susannah Cecelia, who became Edna’s mother. Susan, as she was called, was the youngest of nine in a family of seven girls and two boys. In due course she married Edna’s father, Johnson Eliot Wright, son of Benjamin C. Wright, who was born in Alexandria, VA, when it was still part of the District of Columbia. Edna’s father had a great uncle, Robert Wright, who was Provost Marshal of Bladensburg during the Civil War. Robert had inherited a gold watch as the then eldest survivor of another Wright which was inscribed: “Prescribed to ------ Wright by General Lafayette, for taking care of him while he was wounded.” Edna’s father had another great uncle, Judge James Wright, who was Chief Librarian of the Department of Justice. As for himself, “father” Wright had served in the Finance Branch of the War Department. Upon retirement, a formal testimonial acclaimed him to be “a Christian and a polished gentleman of the old school, very loyal, and an assiduous worker.” He was also a good husband, and together with Susan spawned eight children, six girls and two boys, of which our Edna was the eldest. In his retirement, he became the secretary for the Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of DC, a position in which he continued his “loyalty” and “assiduous” working habits until his death.

Before moving on, mention must be made of Edna’s father’s older brother, Herbert. He began work at 16 as a telegrapher for the Baltimore and Ohio RR, where he eventually rose to become Chief Operator. He next switched to Western Union as chief night operator of its Washington office. Then followed a brief stint with United Press. From there he moved on to become a telegrapher in the Adjutant General’s Office of the War Department, where he became renowned as “the best and fastest” in the city. He would eventually complete 30 years of government service, including being in charge of the cable and telegraph work of the entire military establishment, including the coding/decoding of official cipher messages. Much of the latter traffic during WWI was, of course, “of the highest national importance.” Because of his efficiency and expertise, his tenure was extended for three consecutive two year terms beyond the then mandatory retirement age of 70. Surely such performance is a proper matter of family pride and warrants this brief memorial paragraph. Now, back to our story.

In sharp contrast to the geographical stability of the Wright clan, so deeply rooted in the general area of the nation’s capital (and a tradition from which Edna was to deviate with happy results that shall bear on the substance of our story), the Wiggs clan persisted in its nomadic heritage. We pick up the thread of this tribal evolution with Al’s grandfather, Matthew Wigglesworth (1794-1873) who migrated from Liverpool, England, via Canada, to Palmyra, New York. There is no accounting for how this shoemaker so directly descended from English nobility happened initially to settle in this small village, of less than 4,000 inhabitants, located on the Barge Canal south east of Rochester in west central New York. (Joseph Smith also lived in Palmyra, and published the Book of Mormon there.) Not to worry, the Wiggs didn’t remain there long. Somewhere along the way Matt married an Elizabeth Hudson, said to be related to the Henry Hudson. For our purposes, at least, their crowning achievement was son Thomas Hudson Wigglesworth, Al’s father.

With the advent of Tom Wigglesworth at Palmyra on 31 Jul 1835 this story really (we sincerely hope) “takes off” at last, and your interlocutor at once suffers an embarrassment of riches with respect to source material. The simple fact is, Tom Wigglesworth was quite a man! Our fervent hope is that we may do proper justice to his truly frontier’s-man character. The latter was quick to reveal itself. He ran away from home at age 13, all the way to Kentucky. Though he would never grow to be a big man, even as a youngster he was evidently both sturdy and audacious, becoming an axeman for the Louisville and Nashville RR. He was also observant and ambitious, and so returned to New York at 19 to study trigonometry in order to become an engineer. Then it was back south again, this time to Tennessee. It was at Fountain Head, TN, that he met Ann Spradlin, whom he married on 14 May 1863. They would have seven offspring, numbering five boys (including their last child who would survive only two years in Colorado) and two girls. Al would be the fifth child and third son. Perhaps his placement in the middle of this considerable constellation of “kinder-folk” accounts for his calm, moderate and totally balanced temperament and uncommon humility.

As for Al’s brothers and sisters, not too much is known, except for younger sister Emily Elizabeth (later Mrs W. H. Howard of Animas City, CO, whom we shall meet again briefly incident to the introduction of the first Silver Vista observation coach on the Durango-Silverton RR run on 22 Jun 1947), and brother William Hudson Wigglesworth and his son James. Hill was born in Parksville, KY in 1866, and traveled to Durango with his parents in 1881 where he died in 1946. At various times in the interim he held nearly every public office in Durango and La Plata county, serving as Durango city manager for 14 years, and as city and county engineer, Magistrate and justice of the peace. During his colorful engineering career he also spent time in New Mexico, Arizona, Florida and Mexico. He worked on the construction of the Durango-Silverton RR run and later as surveyor on the Crystal River RR in Pitkin county. Then followed two winters in Chihuahua, Mexico, on the RR from Juarez toward the Sierra Madre mountains. He also surveyed Indian allotments and irrigation canals around Ignacio, CO, and the Perin’s Peak RR.

He went to AZ in 1910 for four years surveying Indian allotments to the Papago. He also did a stint as mill man at a gold mine, and assistant city engineer in Ft. Lauderdale, FL, eventually returning to Durango where he surveyed the water system which serves the city even today, and also built the Narraguinnep Reservoir north of Cortez. The nomadic instinct of their Norseman-Norman heritage clearly lived on through Tom and sons Bill and Al Wigglesworth. These fellows really got around. So did Bill’s son, Major James Wigglesworth. A graduate engineer, he served nine years in the state highway department. Then, after extensive military training in OK, KS and MS, Jim saw four years service beginning in Jan 1945 as a ground liaison officer with the 7th and Patton’s 3rd Armies in France, Germany, and Austria, penetrating to the Enns river link-up with the Russians. With the peace he reverted to Augsburg, Bavaria, where he was charged with feeding, housing, and relocating displaced persons – an experience that would stand him in good stead following his discharge. He returned to Durango to become city manager in Jan 1946, following in his Dad’s footsteps. And, as with Dad’s footsteps, Jim’s soon started spreading out. After five years, he resigned his Durango post to become city manager of Russell, KS, at a substantially larger salary. The pioneering spirit apparently dies hard.

Meanwhile, and before dealing with the remarkable engineering feats of old Tom Wiggs, what do we know about his wife, Ann Spradlin? (Hey! You can’t tell the players without a score card. Maybe you should be taking notes.) Well, as we’ve mentioned, Tom caught up with her in TN, but before going forward, we had best take a short look backward. On the paternal side of Ann’s family tree there is a dearth of information. We only know that her father’s name was John, and that he married Emily Hodges on 22 May 1839. We are a sprite more fortunate with respect to the maternal side of her family ancestry. Emily Hodges was said to be a cousin of Henry Clay. Beyond that, we are able to trace back two more generations to an Elizabeth Clay married to an Isham Hodges (born 18 May 1763). They owned 600 acres in Henry county, VA (on the southern border, on a line between Roanoke and Greensboro). Regrettably, this attractive if modest estate was confiscated by the government, since Isham unaccountably remained a British citizen. So, all Isham really “left” (and his will of 14 May 1782 is still on file and suitably inscribed with “his mark”) was 11 children. Finally, we know that Ann Spradlin died in Durango on 19 Dec 1934, (Whew! It’s Miller time!) Now, we can proceed with the story of Tom (and then Al) Wigglesworth.

We left off with Tom in KY after completing his math studies in NY, and we noted his marriage and the subsequent spawning of his seven children. Now, let us take up Tom’s engineering career, which was largely performed in the service of our then still expanding RR system. Son William recorded (Pathfinders of the San Juan Country – Vol III) that the early history of the RRs of the San Juan Basin (most of which were Tom’s work) was eloquent testimony to Tom’s legerdemain as RR location and construction engineer. He went on to recount that Tom started his career in a RR working party under his older brother John around Fountain Head, TN. John was location and construction engineer for the Louisville and Tennessee RR. During the Civil War Tom served as a freight conductor on that road. When the war was over and RR building was resumed, Tom returned to his first work and rapidly advanced from axeman to rodman, and then to instrument man. Then he was appointed location and construction engineer for the Knoxville branch of the Louisville & Nashville RR. After service with several RRs around Parksville, Elizabethtown and Louisville, KY, Tom answered the call of the West, and took off to check out the Black Hills of SD in 1877.

He then returned to his homeland for a brief respite, but by 1878 he was back in the West to stay, and working for the Denver and Rio Grande RR. It was then that his reputation as a pioneer RR locating and construction engineer was really made, beginning with his settling in around Durango, CO, where he was to die on 16 Mar 1909. He established some 600 miles of track in this mountainous southwest CO area, including putting the first narrow gauge line into the Rockies, and the surveying of the famous Moffatt tunnel (a 6.4 mile tube at 9,100 feet across the Continental Divide and piercing James Peak WNW of Denver), which was completed in 1922-27 after his death. As Chief Engineer he also put in the lines from Durango to Mancos and Dolores, and from Colorado Springs to Cripple Creek and to Leadville, of which latter he said, “Other engineers said it couldn’t be done, but there it is.” Incidentally, Cripple Creek once surrendered $25 million in gold in one year. In the early 1980’s it was reactivated when a steep rise in gold prices made mining there profitable once again. Leadville, formerly Oro (Gold) City, is the highest (over 10,000 feet) incorporated city in the USA. Gold in its California Gulch attracted 5,000 people into a five mile strip there within four months in 1860.

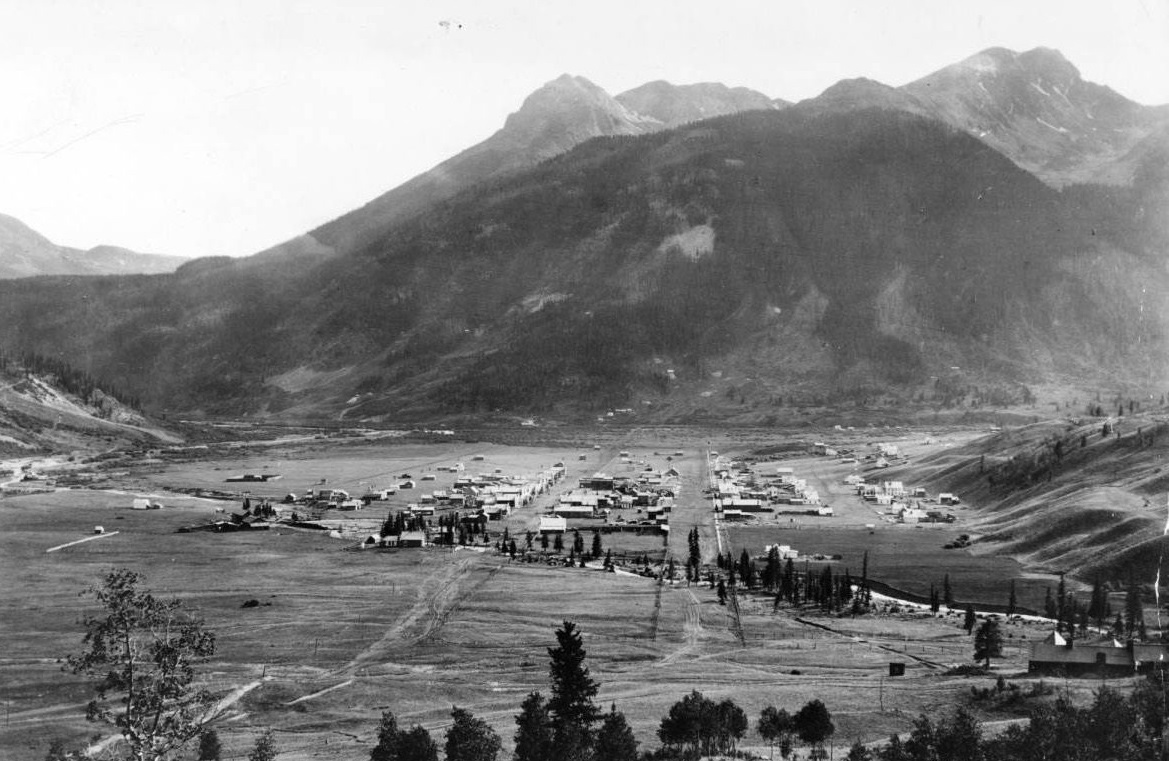

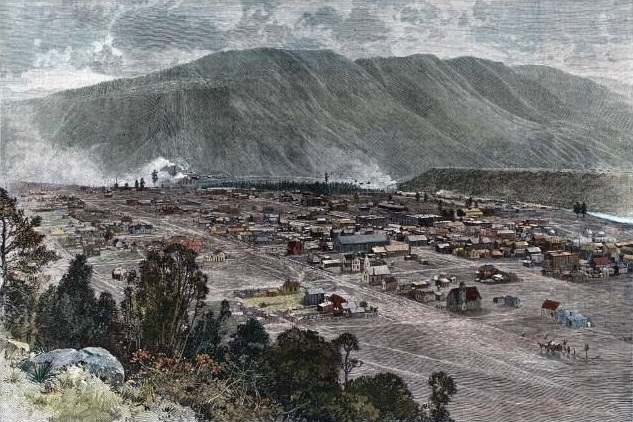

You may have noted that we said that Tom settled in at Durango in 1878, whereas we reported earlier how son Bill (and presumably the rest of the family) went west with Tom in 1881. Actually, Al’s memoirs will clear up this seeming discrepancy. (Be patient! We promise that we shall get to them, and soon!) What happened was that the family joined Tom (who had preceded them to CO) in the spring of 1881. A complicating factor was that Durango (a name strangely of Moorish origin and meaning concourse or meeting place) was not established until 1880. Be that as it may, and thanks largely to Tom Wiggs and the RR, a concourse it certainly became. In the halcyon period of 1900-1912 it had four RRs converging from the four cardinal points of the compass.

Now, you might say that Durango and the RR were almost a “chicken and egg” proposition as to which came first, but you would be wrong (and in any event the Wiggs clan would have been on hand for the greeting). Actually, it was RR policy simply to bypass non-cooperative towns, leaving them to wither and die, even as new towns along the chosen route were, as was Durango, actually designed by the RR. In fact, the present day Animas City (two miles north of Durango on the Durango-Silverton run) is the second so-named city, the first (15 miles north of Durango) having been supplanted thereby through RR manipulation. The D&RG15 was perfectly willing to work with charitably disposed communities. This might mean the donation of a right-of-way or a depot site, the purchase of RR stock, or even help in grading part of the line. If such aid was not forthcoming, the RR just proceeded to establish a rival community. Such is the alleged American Way. “Animas City,” by the way, is really a sort of shorthand for the full name of the river for which it is named – River of Souls Lost In Purgatory – which in itself gives you as good an idea as anything else of the tortuous, testing nature of that formidable territory.

Durango (1986 pop. – 11,400), variously called the Sagebrush Metropolis, the Magic Metropolis, the “Denver of Southern Colorado,” and even more accurately “the child of the RR,” really (as with other settlements in the area) owed its existence to the gold and silver found in the San Juan Mountains. (The heavily mined 14,150-foot Mt. Sneffels yielded $35 million in gold and silver by 1889.) It’s future was assured when the San Juan & New York Smelter was relocated there from Silverton in 1880. Durango was not itself a conventional frontier town. It was a miracle of “instant urbanization.” It had three newspapers by 1881, which is two more than the capital city of the leading nation of the free world – Washington DC – had in 1981. And these weren’t light-weight entries common to many boom-towns. In fact, one of the area papers (nearby Ouray’s Solid Muldoon) counted Queen Victoria of England among its subscribers. Typical of its prosperity and sophistication was a Christmas newspaper ad of the period: Fur-get and fur-give!

Of course, Durango also suffered the maladies of most fast-growing mining towns: shortages, high prices, lawlessness, violence – and the ubiquitous female “prospectors” whom they called shady ladies of the eighties. In Durango they occupied a two-block strip between the RR spur and the Animas river. The houses included the Variety Theatre, the Silver Bell, the Clipper, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon – a curious name for the only one devoted to lynch-conscious blacks, and simply Bessie’s, Jennie’s, Hattie’s, and Nellie’s. More generously, they all went under the euphemism of “dance halls.” Indicative of the times is an epitaph found upon a tombstone in nearby Ouray (“Your-A” – for a famous multi-lingual Ute Indian chief), thus:

Here

lie the bones of poor old Charlotte,

Born a virgin but died a

harlot;

For eighteen years she preserved her virginity,

A

damn good record for this vicinity.

Notorious neighbors and visitors from nearby Creede (68 miles to the northeast) included Robert Ford, Martha Cannary and William Barclay Masterson. You say they don’t ring a bell? How quickly we forget. Ford was the bozo who shot Jesse James in the back and got a dose of the same for his trouble 10 fearful years later. As for Martha, perhaps you’d recall her more easily as Calamity Jane. Bat Masterson, of course was the legendary non-gun-drawing peace officer imported to bring law and order to Silverton before moving on to New York as a newspaperman. More recently, attention has been drawn to the area by artist/rancher Fred Harman, originator of the comic strip Red Ryder. Then there was Alferd (sic) Packer, the sole survivor of a six man trek into the San Juan Mountains in the winter of 1873. With the Spring thaw, Packer was found guilty of murder and cannibalism. Years later the whimsical students at the University of Colorado would vote to name their dining hall the Alferd E. Packer Grill. So it goes…

By now you may have forgotten that this is purported to be the saga of the Wigglesworth clan. Remember, though, that you were warned at the outset of this segment that we confronted a wealth of material. Anyhow, you surely must now have a much better feel for and flavor of the times and the territory, and that’s the whole point of the immediately preceding mish-mash. It was sort of a stage setting for the scene into which our central hero, Doctor Al, would be introduced at age 9 in 1881. Before moving on to Al, however, we should complete the dossier on his father, Tom. (Even so, we shall reserve to the next chapter the story of what we shall choose to regard as Tom’s crowning engineering achievement – the locating and construction of the D&RG’s Durango-Silverton line in 1881-82.) Let us begin our summing up by simply quoting in full his biography from the Biographical Directory of Railway Officials of America, thus:

Born 31 Jul 1835 at Palmyra, NY; entered RR service 19 Nov 1854, since which he has been consecutively (1854-67) axeman, rodman, assistant resident and division engineer, Louisville & Nashville RR; (1867-72) division engineer, Elizabethtown & Paducah RR; (1872-73) chief engineer, Memphis & New Orleans RR} (1874) engaged in building Cecilian branch, Elizabeth & Paducah RR; (1874-77) contractor, Louisville & Nashville RR; (1879-84) on Denver & Rio Grande as follows: (May-Jun 1879) leveler; (Jun 1879-Jan 1880) locating engineer in charge of construction of Silverton branch; (Jan 1890-Sep 1882) in charge of Utah extension; (Sep 1982-Feb 1884) general engineering work; (Apr 1887) also chief engineer Utah Midland RR: (present: 1893) chief engineer for construction, Crystal River RR.

Well, so much for the nitty-gritty facts, but that still doesn’t tell you very much about the character of the man. So, we have yet another biographical synopsis which elaborates a little, and we include it here in full:

Mr. Wigglesworth was born in New York in 1835. He was just old enough, after he received some engineering training, to be useful to the Union Army in the Civil War. He built and maintained track, especially in Tennessee, during that time. After other ventures in his chosen work, he made his appearance in Colorado in 1879. He spent the next two years with the D&RG, surveying and constructing crews that were then building a railroad from Antonito (100 miles east) to Durango. [The Antonio (CO) to Chama (NM) section of this line survives as the tourist-attracting Cumbres-Toltec Scenic Railway to this day.] In 1886, he was chief engineer with the Midland Terminal in Eastern Colorado. As chief engineer and constructor, he was responsible for three pieces of railroad in the San Juan:

The D&RG from Durango to Silverton, 45.63 miles, in 1881-82. The story is told (and a picture shows) that during surveying through the canyon just north of Rockwood, men had to be let down by ropes from the top of the mountain above, to peck out a line along the granite cliffs. To look at it one does not doubt.

The south part of the RGS16 from Durango to Dolores, 58.75 miles, in 1890-91.

An extension of the Silverton Northern from Eureka to Animas Forks, four miles, in 1904 (which entailed 7-1/2% grades – the maximum for steam railroads].

Wigglesworth made many more railroad surveys in the San Juan than any other engineer, which rather bespeaks his ability. Following is a list of those which can be verified:

From Las Animas River up to Hermosa Creek and dawn Scotch Creek to Rico, then down the Dolores River, through Lost Canyon and over Chama Pass to Durango, in 1881.

From Silverton to Red Mountain and Ironton Park, in 1881.

Down the Las Animas River, down the La Plata River and down the Mancos River to the Farmington area, as part of a projected RR to Phoenix and Los Angeles, in 1890-91.

From Algodones, NM, to Farmington and Durango areas, and thence to Utah, as part of a proposed RR to Salt Lake.

From Durango to Clifton, AZ, in 1901.

From Animas Forks to Lake City in 1904.

“Old Wig’s” ingenuity was remarkable. [Original manuscript note: He was familiarly known in this country as Old Wig. Other appellations recently used for him have no basis in fact.] He was able to surmount almost any difficulty with some makeshift of his om. Vest Day tells of a survey crew crossing the AZ desert with no way to measure the mileage. Wigglesworth tied a can to the buggy wheel and then the men (three of them) took turns of one hour each, counting the bangs of the can as it hit the ground. The number of revolutions times the circumference of the wheel quite accurately determined the mileage for that day.

“Old Wig” was notorious for his “Kings English.” He could tear off a lot of it to fit any and all occasions. He had a quick temper, an acid tongue, and was exacting with his employees. Yet he could be very kind. Marion Speer tells of working for him as a “nipper” on the railroad from Eureka to Animas Forks. He was only a young lad and had to carry heavy tools from the graders to the blacksmith’s shop for sharpening and then carry them back to the graders. Mr. Wigglesworth told him he’d have to let him go as the work was too heavy for him. Marion started to bawl and said he had to have the money to go to mining school. “Wig” not only rehired him, but gave him a helper besides.

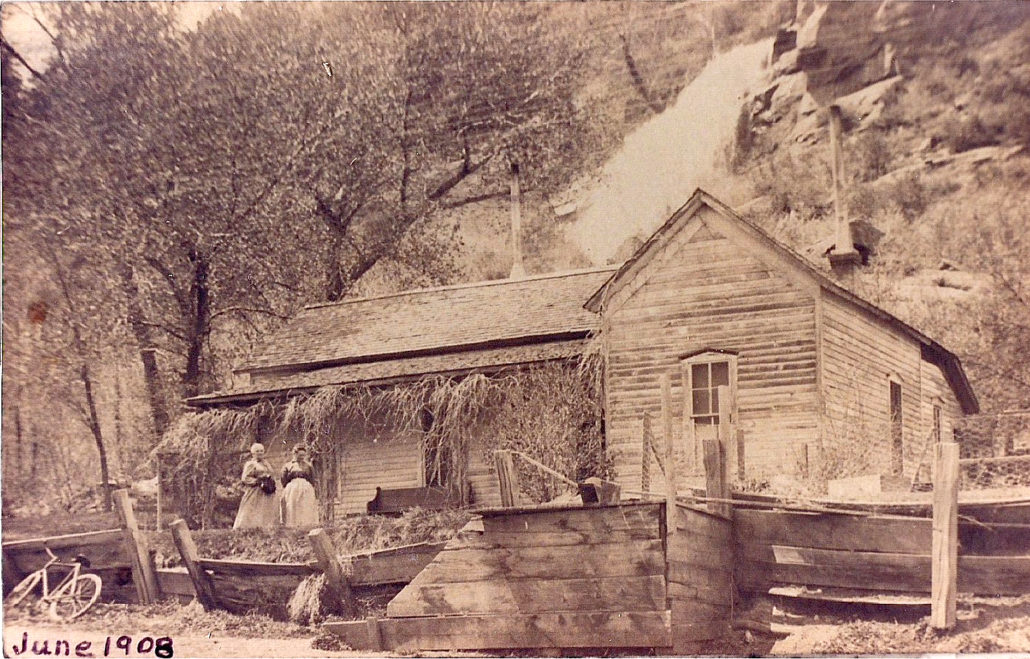

Soon after Wigglesworth started work in the area, he purchased land for a farm, five miles north of Durango and called it the “Waterfall Ranch.” Here he built a home and lived until his death in 1909. Perhaps his greatest love was this farm and his farm work.

When Richard Cunningham bought the property and started peeling the old paper off the walls in the living room and two bedrooms, he found the bottom layer to be those huge, linen RR survey maps. He and his wife removed them as carefully as possible and were in the process of piecing them together when the house burned down in Nov 1953. [Pioneers of the San Juan Country – Vol 1]

Well, Old Wig must by now be coming into somewhat sharper focus in your mind’s eye, but we still haven’t taken full measure of this hearty railroad pioneer. As Isadora Duncan wrote in her autobiography, “There is the vision our friends have of us; the vision we have of ourselves: and the vision our lover has of us. Also, the vision our enemies have of us – all of these visions are different.” Amen! There can be no doubt that Old Wig pleased his main boss, the redoubtable Otto Mears, since the latter kept re-hiring him. And, Otto was a rugged individualist of the first order who demanded of his key employees exactly what he demanded of himself – everything – total commitment plus! (He once built a lumber mill with no other tool than a hand saw – and no nails! He scratched out 450 miles of toll roads in the San Juan Mountains, of which perhaps the most famous is the so-called Million Dollar Highway. Natives cheerfully debate as to whether the name derives from its original construction from mine ore leavings, the huge cost of rebuilding it to accommodate modern vehicular traffic, or in testimony to its breath-taking scenery. Linking Silverton and Ouray, it is one of the most spectacular auto routes in the nation. Popularly known today as US 550, it is really only the straight six mile stretch overlying the original toll road.

Otto also fulfilled a government mail route commitment, personally when need be, through biting sub-zero temperatures, heavy snows, near tornado level winds and soft spring slush that could engulf a man to his armpits. He was the money angel and driving force of the D&RG. (Curiously, Otto’s only RR venture east of CO was the construction of the now defunct Washington DC-Chesapeake Beach MD Railway.) Tom Wigglesworth was Otto’s kind of man’s man. But Old Wig also had the respect and admiration of his employees down the line. However varied the perspective, from whatever angle you look at him, Tom Wiggs comes off well. For proof, we here excerpt an article by George Vest Day, The Pathfinder of the San Juan – As Crew Members Remember Him, from Pioneers of the San Juan Country – Vol III:

Recorded history has a tendency to emphasize the importance of those whose efforts aided community progress, if those efforts were richly rewarded in dollars and cents; while those who assisted the hard way, with only modest financial returns, are merely casually mentioned.

I do not wish to detract from the well deserved credit of Otto Mears for his toll and railroads, but to point out, little has been written about the engineers and crew members who found the way, worked out the grades and measured the distances, in short, those who actually made the construction of these roads possible.

This article is prompted by the desire to acquaint the present generation and its children with one of the latter, whose substantial achievements had a most important part in making the San Juan Basin what it is today; that great old engineer and most unforgettable character, Thomas H. Wigglesworth.

One has only to travel over the Durango to Silverton Railway, the Durango to Rico portion of the Rio Grande Southern or the routes of the now abandoned Otto Mears RR empire to appreciate the almost superhuman engineering feats that won Mr. Wigglesworth the appellation, “Pathfinder of the San Juan.” Thousands of persons visit here every year to view these wonders without knowing to whom credit is due.

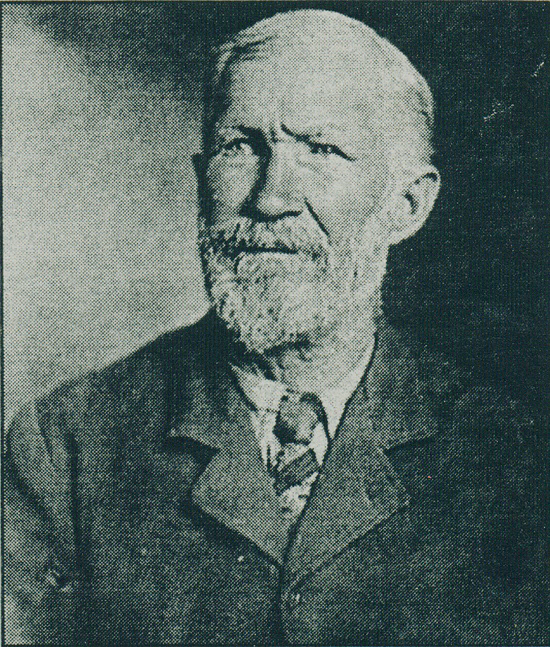

My earliest remembrance of Thomas H. Wigglesworth dates back to 1894 when my father, David F. Day, was Indian Agent at Ignacio. He had been employed to make a survey for a large portion of the ditches and canals that now carry water to Reservation land. I was just a lad of 14, but I still have a vivid picture of him in my memory.

He was not a large man but exceedingly wiry. His face was red from much out-of-door living. His ever present Van Dyke beard favored a goatee angle. Time had slightly grayed his hair and dimmed his eyes. He usually wore a pair of heavy lensed glasses on the tip of his nose, so he could look through them with a minimum of effort, when the occasion demanded. His uniform on location consisted of khaki trousers and shirt, the former tucked in a pair of khaki leggings.

His crew members in late years referred to him as “Sunny Jim,” because of his resemblance to Sunny Jim on the package of Force, the breakfast food most favored at the moment. The reference to Force was an apt one, because, believe me, it was force that constituted the make up of T. H. Wigglesworth. At his time in life, 59, the average man is looking for a permanent seat in an easy chair. Not T. H. W.! Most of his career in this section was ahead of him.

During his Reservation assignment it was frequently necessary to utilize the services of Indians as rodmen or to assist in various other ways. As the help spoke very little English, and in general assumed a “no savvy” attitude, it was essential for “Chief Wig,” as he was affectionately known, to produce a vocabulary to fit the occasion. He did! The finished product reached such a state of perfection it really did not sound like profanity at all. Apparently the Indians thought it was just professional lingo and grinned in such a way it sent his blood pressure soaring. When his pent up emotions needed a safety valve he could and did swear so forcefully, it is well recalled to this day.

I well remember the first night at the Basin Creek camp [6 miles south of Durango.] Sixteen men were seated around the camp fire. Not a bite to eat! The cook, who had promised to take charge of the food department, failed to materialize. I had heard Chief Wigglesworth give vent to vitriolic remarks at the agency, but when he arrived to find this state of affairs his agency remarks were but feeble illustrations of his ability for tossing words. No cook living or dead could have escaped being singed.

* * *

(The Chief) never mingled or kidded with the boys or became familiar with them. He was never grouchy or fault-finding. But if he had reason to be displeased he expressed himself right now in no uncertain terms. However, he weighed things from every angle. If he found that he had made a mistake he never failed to rectify it. I am sure all his old crew members would gladly join me in this tribute. He was a marvelous engineer, a just and square man, and one whose life was replete with kind deeds.

One could hardly improve on the latter as a fitting epitaph to The Chief. We won’t even try, lest we muddy the waters. Suffice it to say that now we might all easily recognize the man if it were only possible ta meet him. Beyond that, the probability is strong that we should all have wished to meet him and would have enjoyed such a meeting – all of which prompts a few reflections on the value and lessons of biography. Culling through the personal histories of those who preceded us, whether family or not, we become ever more aware of the continuity and kinship of all humanity. We’re all part, after all, of a single giant tapestry of life. At the same time, we become keenly aware of how fleeting life is, and are increasingly impressed that we too shall pass from this earthly scene. Finally, and happily, there is the merest hint for hope – precisely through biography – that somehow, in fact, we shall live on.

The true history of the United States is the history of transportation – Phillip Guedella

Having proposed a fitting epitaph for Thomas Hudson Wigglesworth, let us now salute his most lasting monument – the Durango-Silverton Railway. Unique in its conception and execution, this 45 mile spur of track is equally unique in its longevity. It is today the only fully ICC regulated, 100% coal-fired, narrow gauge railway remaining in the United States, and (save for mountain slides, floods and blizzard snows) has been in scheduled continuous service since 1882, celebrating its first 100 years of operations on 13 Jul 1982. As the monument at the Cascade Canyon wye (the 26 mile-post) implies, the “Spirit of Colorado Mountain Railroading” is embodied in this short but tortuous line. No finer monument to any railroad man exists anywhere, nor could one even be imagined.

In 1879, Tom Wigglesworth, then Otto Mears crack location engineer, arrived on site by burro pack train, the surest and safest way over the mountains embracing the area. His preliminary survey reached the Animas valley from Silverton on 8 Oct 1879. The next morning an unprecedented three-foot snow covered the ground and his party fought its way to Animas City where they camped during the night. Tom then returned to complete his construction chores in Antonito, but was back surveying the Durango- Silverton run in the early Spring of 1880, as soon as the weather permitted. Construction work was begun at once, although the location survey was not completed until Jul 1881. Track laying was finished at Silverton in Jul 1882.

The train traverses a remote wilderness area of rare and majestic beauty, part of the San Juan National Forest, following the Animas River gorge. This area is only accessible by railroad, horseback or on foot. Scenes for many Hollywood films about the west have been enriched by its lush but rugged grandeur, notably Mike Todd’s Around The World In 80 Days, and the movie Ticket To Tomahawk featuring Dan Dailey. Other films shot in part on location in the area include: Across The Wide Missouri, Night Passage, Naked Spur, The Denver & The Rio Grande, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. It is the genuine locale of the truly Wild West. No doubt most modern day, city-soft Americans would concede, “It’s a nice place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there.” It is only through Tom Wiggs’ path-finding railroad that they are even offered the option.

How did the engineering marvel known as the Durango-Silverton Railway come to be anyway? Where does one even began to tell this fascinating story? Well, to give credit where credit is due, we shall rely mainly on three excellent sources: Zeke and Russ Wigglesworth’s Ride The High Iron To Yesterday from Trek Along The Navajo Trail; Doris Osterwald’s mile-by-mile guide to the railway entitled, Cinders & Smoke; and Allen Nossaman’s excellent piece, The D&RG Finally Makes It To Silverton in the 100th RR Anniversary issue of The Silverton Standard & The Miner – the longest surviving paper (from 1875) west of the Continental Divide. Given this rich vein to mine, a problem still remains as to where to begin. Perhaps it is only fitting that we start with the material authored by folks named Wigglesworth (two of Tom’s great grandsons,) thus:

The year 1882 was a banner one for Silverton, CO [1986 pop.: 9,032.] That was the year the mines produced $20 million in gold and silver ore (at that time there were some 27 active mines within a 2-1/2 by 1-1/2 mile area,) and it was also the year the RR cane up from Durango. The D&RG was quite a system, and its eventual consolidation with the Rio Grande Western was probably the most important factor in Colorado’s economy except mining. {$300 million in gold and silver rode this 45 miles.)

Silverton, in 1882, was quite a town. Bat Masterson was imported from KS to help maintain the town’s law. The mines were pouring forth riches the like of which King Midas only dreamed. Money was free and easy, the drinks were cheap – if watered – and a ribbon of steel was about to connect the outside world with Silverton.

* * *

A few years before all this, a wealthy and well-known evaluator of men, mountains and railroad tracks, Otto Mears, decided a railroad should be built southward from Silverton to haul away the ore. Looking for men with the knowledge, experience and courage, he decided on a man he’d met and worked with before, Thomas H. Wigglesworth. The choice was apparently a good one. Even then, railroads all over the United States had wound their ways through his figures and across his maps in KY, CO, TN and UT. And, the Silverton was going to get rough before it was finished. It was obviously a choice for narrow gauge track – the only rail that could be pushed through the Animas Canyon. [Obvious? Perhaps to the authors. The infinitely cheaper sub-standard gauge (three feet as opposed to the normal four feet and eight and one-half inches) meant a less wide cut had to be blasted through narrow granite-walled canyons; less wide grades had to be built-up across vast and deep gorges; less heavy rolling stock would be used, which also abetted conquering steeper grades (an unusual 2-1/2% maximum here, although Tom had encountered unbelievable 4% grades out of Antonito through Cumbres Pass into Chama), and permitted less sturdy bridges, and sharper and less expansive curves (although up to 30% curves were accommodated) following wildly meandering canyons could be more readily negotiated.] A track from Silverton to the smelter south of Durango was the answer for which the men at the nines were waiting. [Closed in 1930, this smelter was re-opened during WWII to handle vanadium (used to obtain finer grain steels with improved tensile strength) and uranium – for you know what.]

Selecting a route north from Durango was simple [the authors volunteer]: just follow the canyon of the Animas River. A few minor [?] problems, of course. How push the track through the narrow canyon near Rockwood? How build the roadbed so the river won’t wash it out? What about snow in the winter? Three times the track went out on the highline above Rockwood before rails, ties, boulders, dirt and human sweat pegged it to the cliff-side. In places, the bed is so narrow that you get the impression of flying, because the track and the roadbed cannot be seen from the coach. [North from Rockwood the so-called highline was the most difficult and costly section of the Silverton to construct – $100,000 per mile.] The 900 foot Rockwood Cut took hundreds of carefully placed black powder shots – some drill holes are still visible from the train – to blast clear. Ernest Ingersoll of Harper’s again details the dividends: “Finally, we jolt down the last steep declivity, turn a sharp corner and roll out upon the level railroad bed. And what a sight meets our eyes! The bed has been chiseled out of solid rock until there is made a shelf or ledge wide enough for its rails. From far below comes the roar of a rushing stream, and we gaze fearfully over the beetling edge which the coach rocks so perilously near, down to where a bright green current urges its way between walls of basalt whose jetty hue no sunlight relieves, and upon whose polished sides no jutting point would give any floating thing an instant’s hold.” [Old Ernie always did have a way with words!]

Accidents, too, claimed time and money. A fifty foot section of rail dropped on a leg can make quite a break. Survey stakes were washed out time and again by Spring flooding, only a prelude to what would happen when the trains began running. But a RR construction engineer is a stubborn man. To him, there is only one goal in mind: keep pushing the track out until you arrive at its destination! In all, 47 miles of track had to be laid, bridges had to be built, curves had to be plotted, grades had to be surveyed: a town was waiting for the Iron Rail.

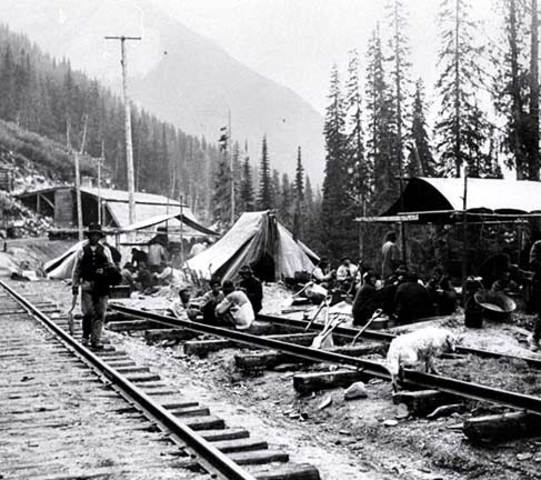

How did these hardy pioneers survive the ordeal presented by the rugged San Juan Mountain country, the so-called Alps of America? The Continental Divide is just six miles east of Silverton – the mining town that wouldn’t quit (from 1860), and the headwaters of the Rio Grande are just another three miles east of that, while some eight miles south of Silverton Snowden Peak rises to more than 13,000 feet. In any event, an article by Ernest Ingersoll in the Apr 1882 issue of Harper’s details the plight of the plucky railroad mountain-busters:

Presently we came upon one of Mr. Wigglesworth’s construction camps – long, low buildings of logs with dirt roofs, where grasses and sunflowers and purple asters make haste to sprout, are grouped without order. Perhaps there will also be an immense tent where the crew eats. Besides the larger houses, inhabited by the engineers, foremen, etc., you will see numbers of little huts about three logs high, roofed flatly with poles, brush and mud, and having only a window-like opening to creep in and out through; or into a sidehill will be pushed small caves with a front wall of stones or mud and a bit of canvas for a door – in these kennels the laboring men [$2.25 per day] find shelter.

As the saying goes, not a pretty sight. In fact, the foregoing is the only construction camp description Doris Osterwald could find in researching her Cinders & Smoke. The further opinion is there ventured that few if any pictures of the camps survive because builders didn’t want prospective investors and stockholders to see the wild terrain and primitive living conditions surrounding the building of these lines, since Easterners were probably already overly disposed to regard such mountain endeavors impossible of success. After a line was completed, of course, publicity pictures were welcome. In any event, Allen Nossaman’s newspaper article next picks up the thread of our story, offering a perspective on these developments from the Silverton end of the prospective railway line:

Silverton, proudly and patiently awaiting its destiny, was in dire need of a boost when the D&RG finally worked its way up the River of Lost Souls In Purgatory [so called because the area was “so hard to get into, and so hard to get out of” in the summer of 1882. The town had been struggling for eight years as one of the highest, and definitely the most remote, of the Colorado mining camps in the post-statehood [1876] era. Since the community’s platting in 1874, a hardy handful of prospectors and merchants had held forth in 9,320 foot high Baker Park [Silverton’s original name] awaiting some viable link with the markets they knew existed for the ores they uncovered… At its founding, Silverton’s closest rail point was Pueblo – 250 miles away by the most favorable route [while during its halcyon period of 1900-12 it marked the confluence of four RR lines]… Old timers felt certain the RR would take the tried and true route into Silverton over the Continental Divide at Stony Pass – even the first piano had come that way. [In fact, the D&RG (like the Ford Motor Co. of the 1970’s) “had a better idea.” They proposed to use the Animas Canyon, and continue on south, deep into New Mexico, to effect the link-up there.]

RR survey parties were in Animas Canyon in Oct 1879, showing the RR’s “hand” to all who would observe. By Nov, the track started due south of Alamosa, and extension contracts were let to the point where the Animas Canyon decisively broadened out into a valley, at a little settlement named Animas City. [Sadly, as recounted earlier, the city fathers and the D&RG failed to see eye-to-eye, so the city was by-passed, the RR effectively digging its grave with every shovel full of dirt turned at its brand new town of Durango.] Grading started north of Animas City as early as Feb 1880, and … arrival in Silverton was joyously predicted everywhere from Oct 1880 to Aug 1881. As the [southern link-up] RR literally inched across the Continental Divide at Cumbres Pass [just about on the CO/NM border directly north of Albuquerque] and began to turn north toward the San Juan Basin, grading work continued in the Animas Canyon into Dec 1880, with as many as 400 men at work preparing roadbed through the challenging canyon.

A harsh winter in 1880-81 provided fodder for skeptics. Heavy snows hampered both work and travel on the “southern route,” and advocacy of the [alternative northern] Del Norte/Rio Grande River approach revived. A fatal accident on the Cumbres Pass route in Apr and the traditional lawlessness accompanying the “end of track” gangs turned many against the new line even before it reached Durango. The D&RG purchase of the popular hot springs at Wagon Wheel Gap on the [northern] Stony Pass route added to the confusion. But the locomotives of the [northern] Rio Grande never saw the head-waters of the Rio Grande on Stony Pass [just east of Silverton.] The company had too much invested in its complex southern approach to the San Juan Mountains, and by Jul 1881, the first work train steamed into Durango. [It arrived from the south, of course, and would become Silverton’s umbilical connection to the world at large. In fact, the Durango Herald of 8 Sep 1881 reported: “A lady purchased a ticket at the D&RG office in this city, this morning, direct to Liverpool, England. We may be ‘out of this world,’ but we’re well connected.”]

Silverton’s hopes for an 1881 rail connection with the outside world faded just as they had for 1880 in the face of the monumental task, but the D&RG general manager D. C. Dodge did come to town in Aug 1881, to begin negotiations on a “fair” depot site and to allay fears that the RR would snub Silverton as it had Animas City. Dodge’s mission was an important one, because the confining San Juans didn’t really offer him any sites for a rival town.