THAT JACK THE HOUSE BUILT

The Alibiography Of An Ordinary Man

By

Jack Wright

Copyright © 1985, Jack Wright

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission of his surviving siblings.

1st

Edition: March, 1985

2nd Edition: March, 2014

3rd

Edition: May 2021

HTML, EPUB, MOBI, and PDF formats are available at https://www.wrightstuff.site

DEDICATION

True love’s the gift which God has

given

To man alone beneath the heaven:

It is not fantasy’s

hot fire,

Whose wishes, soon as granted

fly;

It liveth not in fierce desire,

With

dead desire it doth not die;

It is the secret sympathy,

The

silver link, the silken tie,

Which heart to heart and mind to

mind

In body and in soul, can bind. – Sir Walter Scott

To all the women in my life, from mother to granddaughters; and those beyond the family, particularly the good teachers Mrs. Drake, Sisters Mary Grace, Theresa and Regina; and most especially to the assorted Catherines, each of whom has mightily contributed to my life in a variety of unique ways: my wife Kathleen; daughter KT and Sister Kathleen; the biographer par excellence Catherine Drinker Bowen; and St. Catherine of Siena.

The goal of life is the knowledge and

love,

the vision and enjoyment, of divinity; what

happiness

we get in this life will be through

an imperfect knowledge or

love of God, either

in Himself, or in the mirrorings of

divinity

which we call creatures. – Walter Farrell

CONTENTS

PICTURES

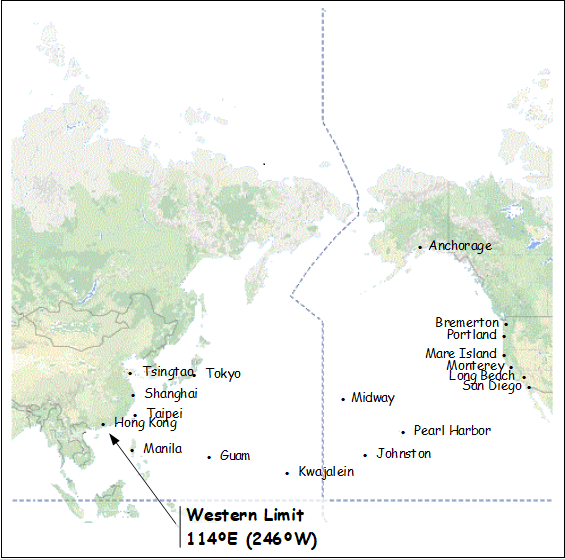

The author’s Ports of Call 1937–1984 (1 of 2)

The author’s Ports of Call 1937–1984 (2 of 2)

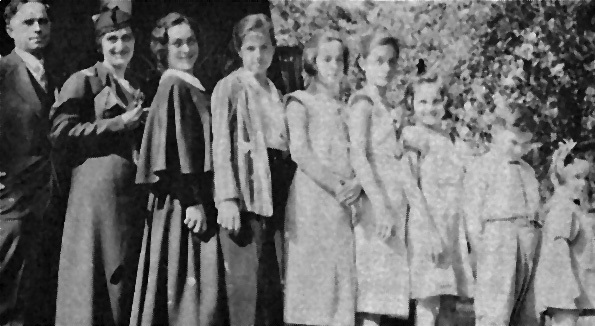

Wright tribe on sister Margaret’s graduation

1961 Corvair – The other air-cooled car

With sister, Margaret, and neighbor Albert Noyes

“I told you! I don’t like milk!”

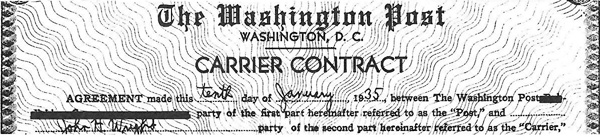

Washington Post newspaper carrier contract

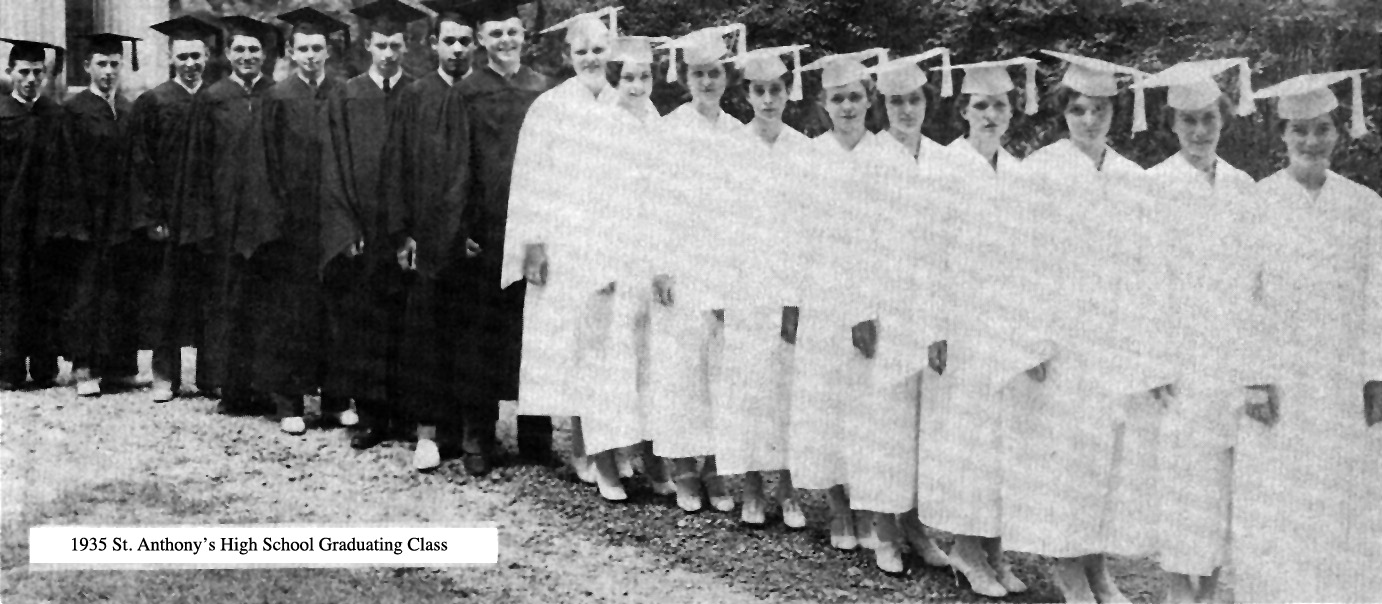

1935 St Anthony’s High School Graduating Class

First Ocean City sojourn together

Johnny Refo – Dave Davenport – Abbot Street, my roommate

Shoulder that butt, buddy, if you don’t want a black eye!

The disk is up! The disk is down! Ready on the firing line!

From the book Annapolis Today – Look who’s walking extra duty

Dave Davenport, Abbot Street, and Frank Hertel

Seaward Terrace – over the Mess Hall

Embarking/Youngster cruise – June 1937

Enroute to Kiel canal in USS Wyoming

Field Day – holy-stoning USS Wyoming deck on Youngster cruise

Funchal, Madeira. It sure beat Bermuda!

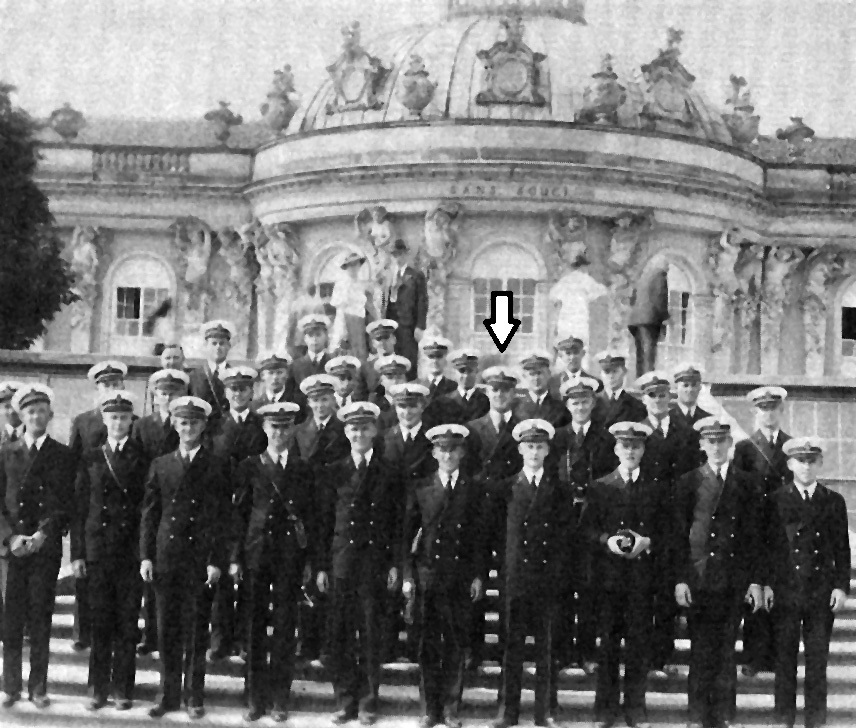

Palace of Frederick the Great at Potsdam

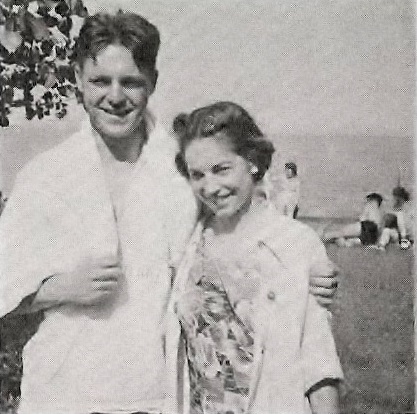

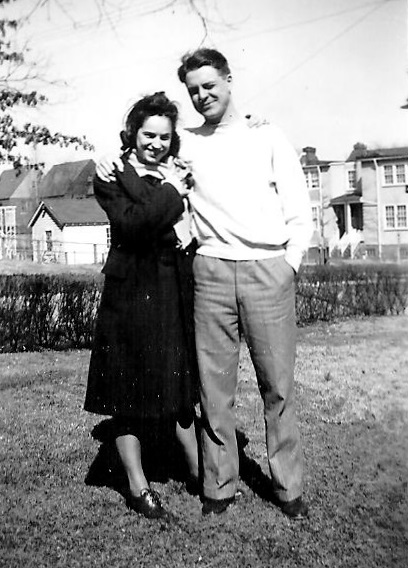

Sailing – with my and roommate’s wives‑to‑be

Letter from Columbia Recording Corporation

“J.” H. Wright – “40”; Don’t believe everything you read in Variety

A snare, a delusion, and a dream

LAST formation – June 1940, 3rd Battalion Terrace

Washington Post graduation announcement, 1940

Times Herald article about USNA graduation, Class of 1940

Jack’s Children at Mt Vernon in 2015

With Pop, Graduation – 6 June 1940

With parents, Graduation – 6 June 1940

With Kathleen and Mom – ENSIGN Wright, USN

With Mom, Graduation – 6 June 1940

With Kathleen – ENSIGN Wright, USN

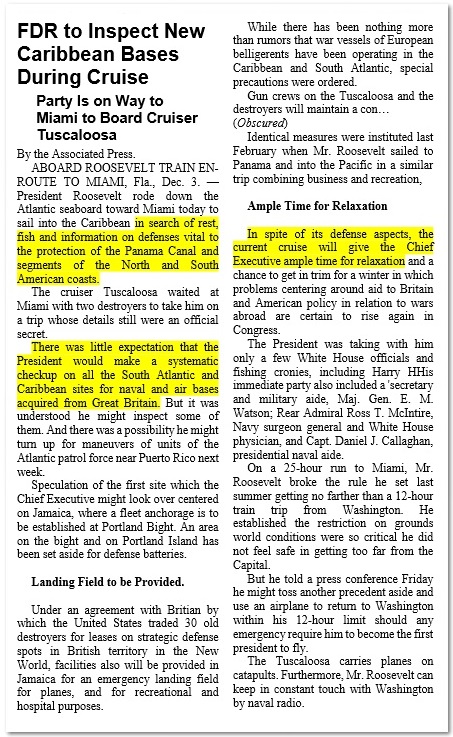

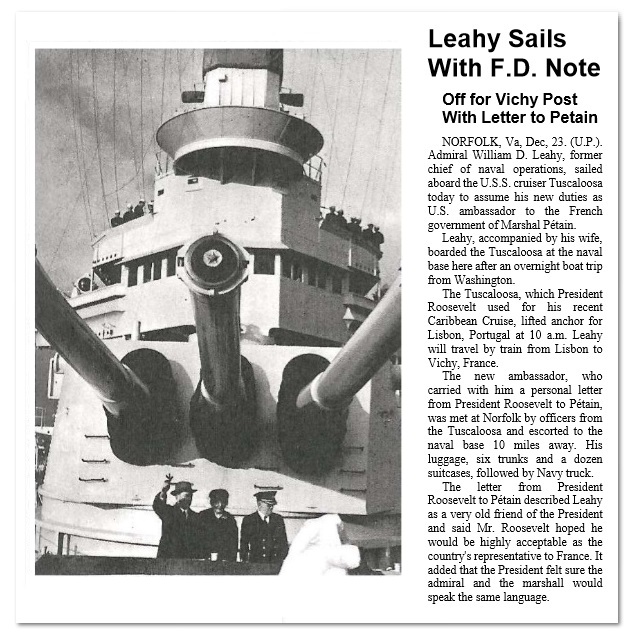

Newspaper item on FDR USS Tuscaloosa voyage, Dec 1940

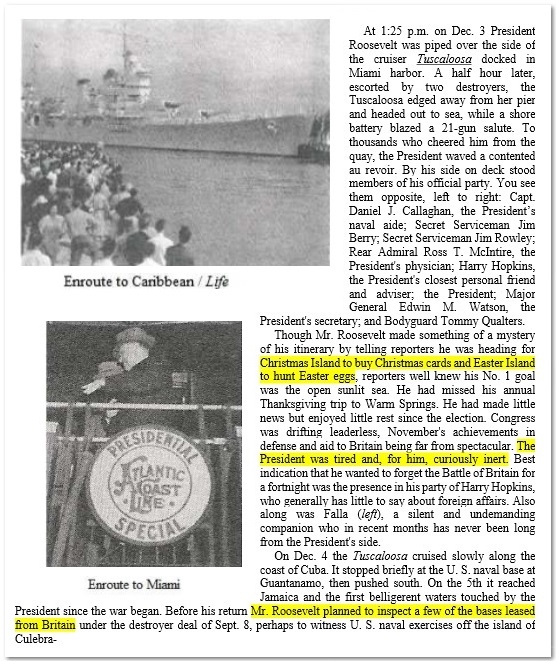

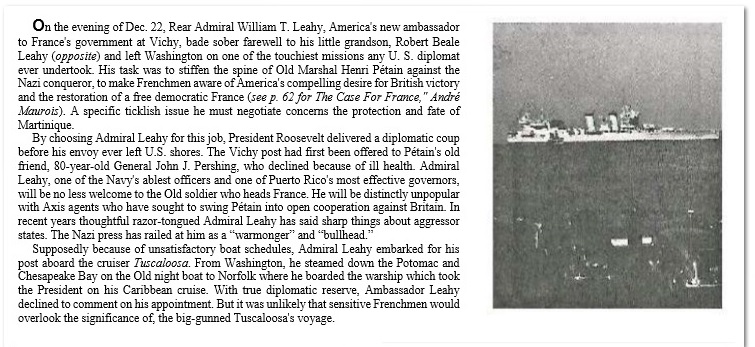

Magazine item on FDR USS Tuscaloosa voyage, Dec 1940

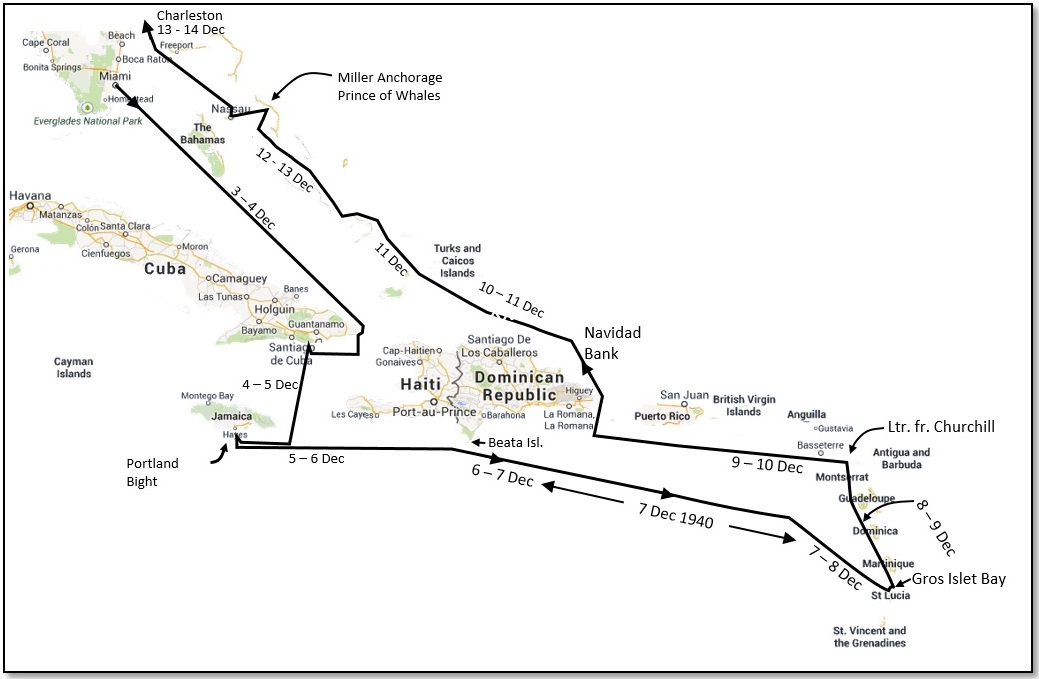

Route of USS Tuscaloosa during 3-14 Dec 1940 with FDR

Admiral-Ambassador Leahy on Tuscaloosa, 22 Dec 1940

It’s all over now! 14 Sep 1942

Flanked by Kirk Krutsch and Tom Walsh

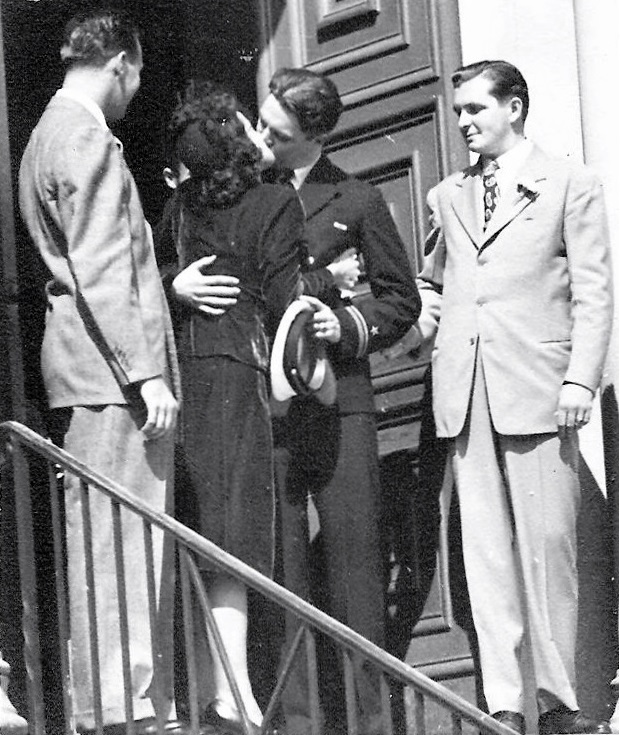

Leaving Wardman Park reception for NYC honeymoon

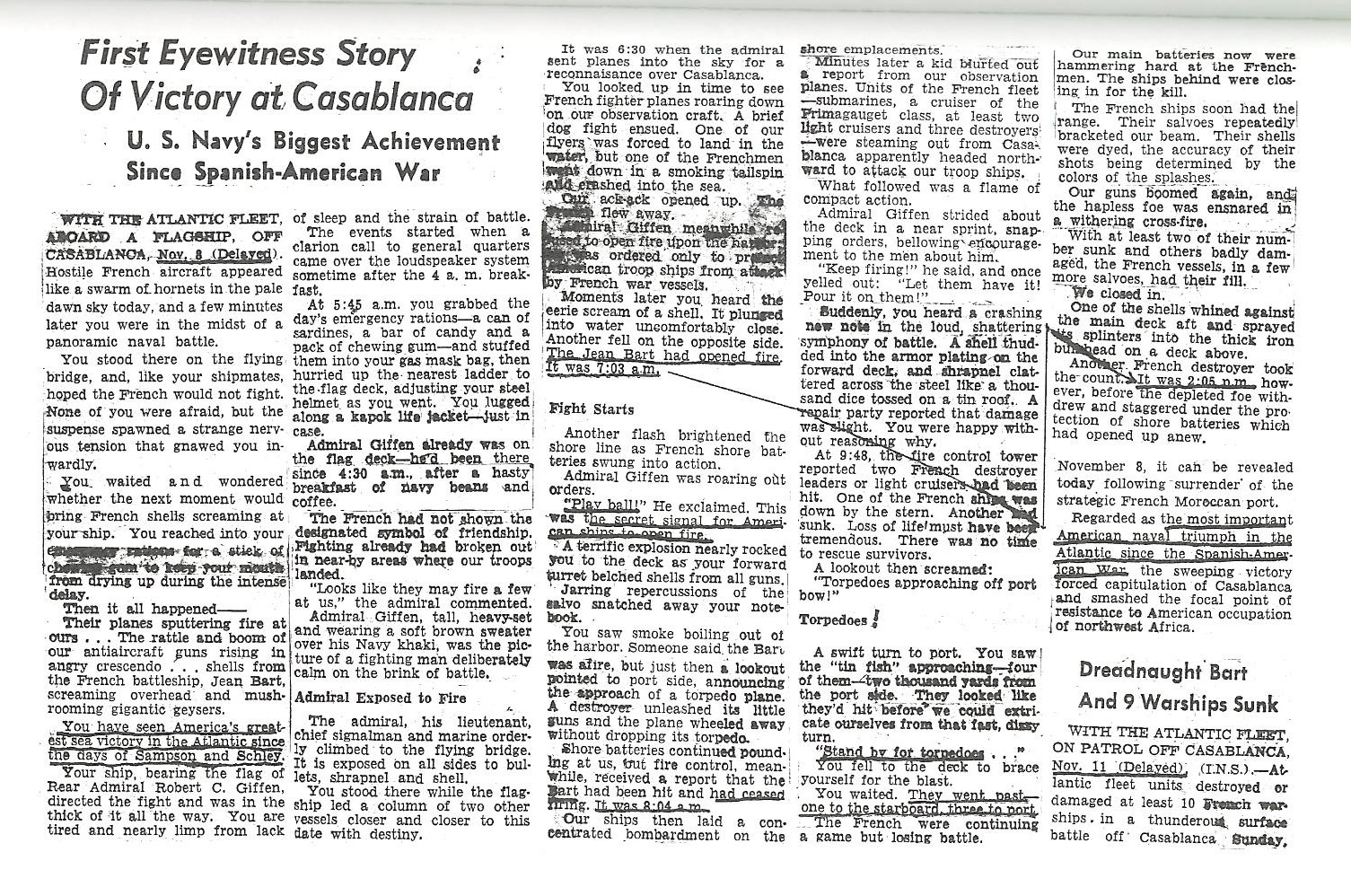

Newspaper item on Casablanca naval battle, November 8, 1942

Picture from Washington Star, August 29, 1943

Crew reaction – Made DC Sunday paper

PG school home – 44, George’s birthplace

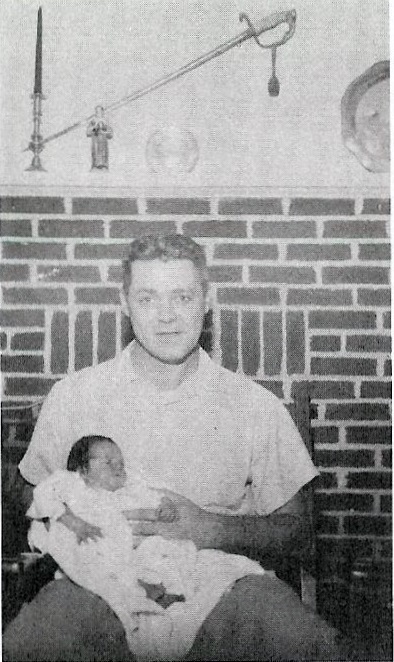

Jack with Geo, Lexington Park California

Lexington Park California (Long Beach)

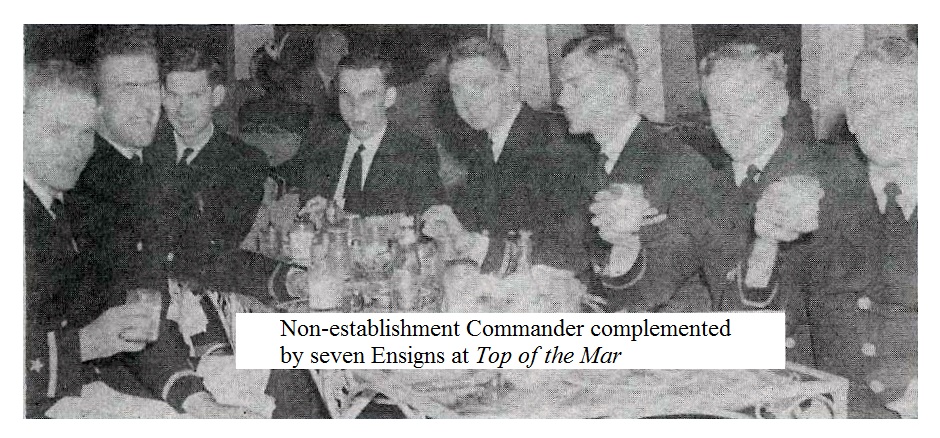

The Commander with proud parents

USS Amsterdam decommissioning crew

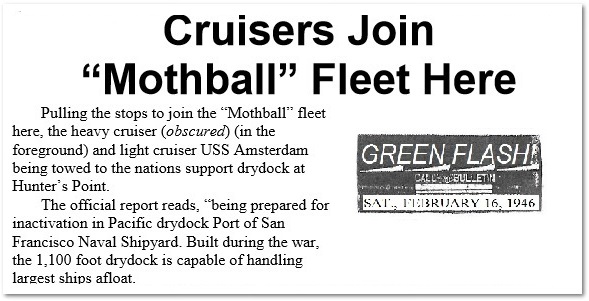

Newspaper item about USS Amsterdam decommissioning

USS Amsterdam entering drydock for decommissioning

Kathleen with Geo – Coral Sea Village – Vallejo, California

Jack with Geo – Coral Sea Village on Mare Island

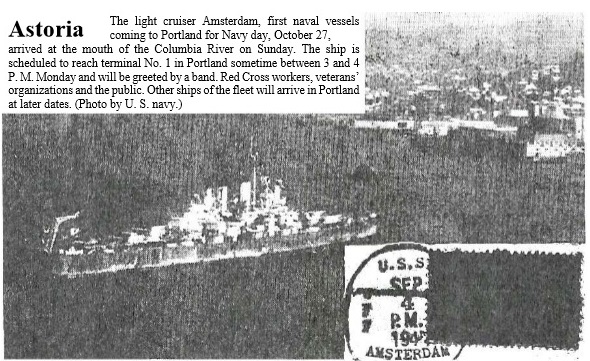

USS Amsterdam arrives in Astoria, Washington

Newspaper clipping about USS Amsterdam’s arrival

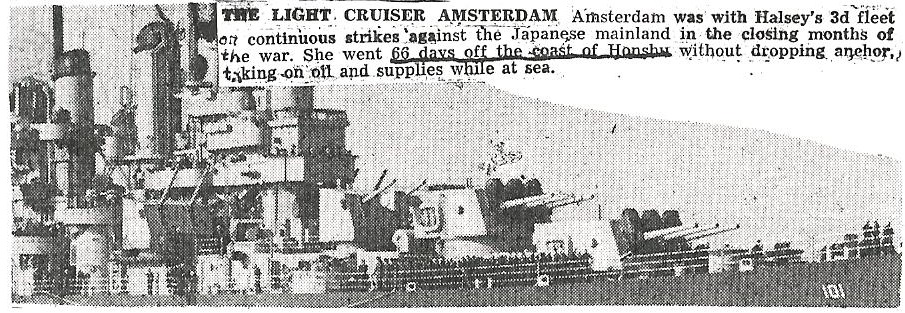

Photo of USS Amsterdam in Astoria

Hood Canal – Sunset Beach – Union, Washington

Anne’s birthplace – Hood Canal

USS Bremerton, CA-130 – My last ship, 1948

Yeoman Brutus – 3 December 1948

Last officer crew – Lt. Rich my r.

Inspiration for my post-service future

Family 26 December 1952 – George 8, JJ 4 months

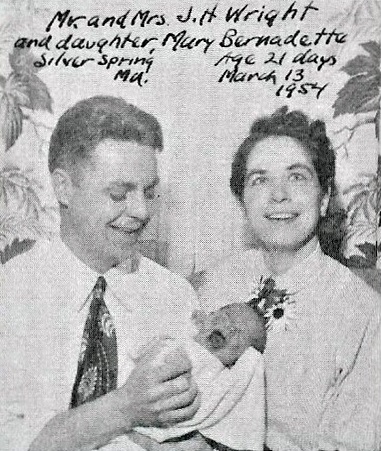

Mary will be heard from – March 1954

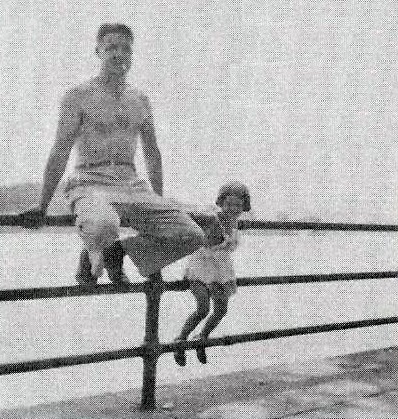

With George at Mayo Beach – June 1954

With Anne at Hains Point – June 1954

KT at 5 days – 5 September 1955

Navy Management Review – September 1959

Navy Management Review – March 1964

SOLIDARITY DAY – June 19, 1966

Meridian MI, Macho-man – December 6, 1966

Kathleen on final approach to Montgomery Air Park (1 of 3)

Kathleen on final approach to Montgomery Air Park (2 of 3)

Kathleen on final approach to Montgomery Air Park (3 of 3)

Author over Bay Bridge – April 13, 1968

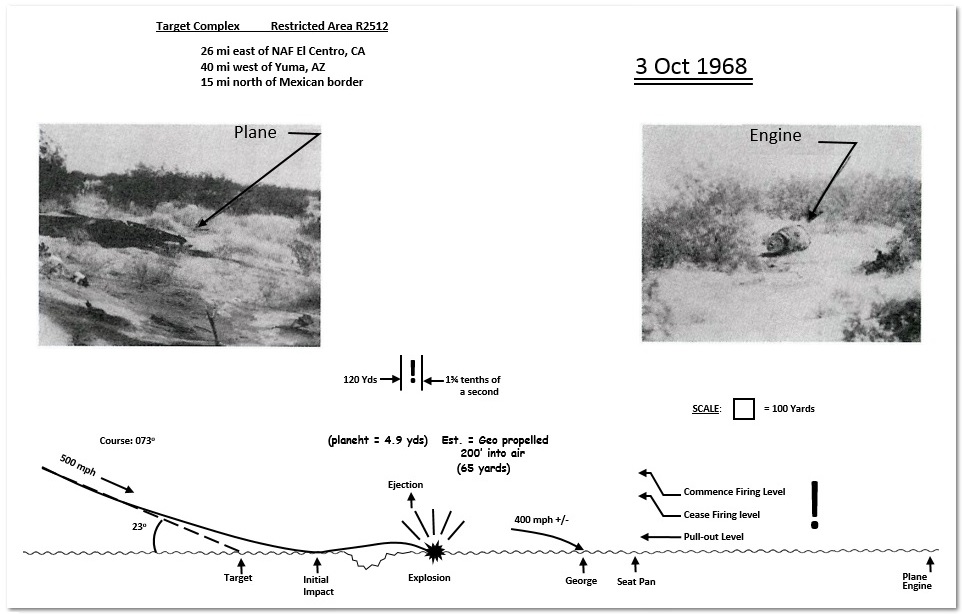

Jack’s hand-drawn schematic of George’s crash

Kathleen approaching Dulles runway 1R, April 13, 1968

Kathleen and Author enroute Harper’s Ferry – December 02, 1967

A night with the Bradys – Howard Johnson’s motel – October 1969

Skyline drive – September 1970

Blue and Gold, Baron and Spouse – Pre-flight at Ocean City, MD

Kathleen over Susquehanna enroute to Harrisburg

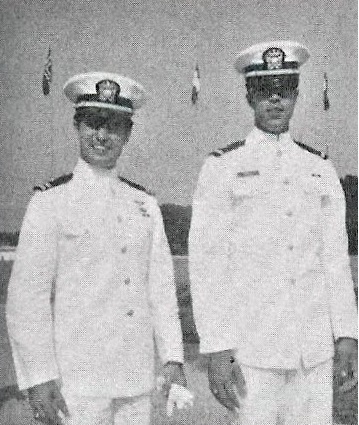

Charlie’s commissioning – October 01, 1971

ERA rally at U.S. Capitol – July 09, 1978

Grand Hotel – Taipei, Taiwan – November 1974

Hilton roof – Hong Kong – November 1974

Enroute Kowloon – Red China border – November 1974

Clark Air Base, Philippines in front of HFDF antenna

Volunteer, Sullivan, and Gates – May 1983

Author at Daytona – January 1980

Mary’s commissioning – February 1981

San Antonio surprise – February 1981

Fighting for my life – August 1972

I finally gave in – January 1980

I told you I had a heart – June 03, 1981

My best medicine pulling me through

Post-op Ocean City therapy – July 1981

40th anniversary bash – August 1982

Alas, Hampton Court really puts Kathleen in the shade

The author’s Ports of Call 1937–1984 (1 of 2)

The author’s Ports of Call 1937–1984 (2 of 2)

DIGITAL EDITION NOTES

This Chapter was added by Charlie and Martha as we produced the digital second and third editions of this work.

The first edition of this work, begun in 1978 before the advent of PCs had a very interesting origin. Jack provides some details of its production in Chapter XXIV. EPILOGUE and also here in Chapter XXII. ANNIVERSARY, where it becomes clear that all of us owe a debt of gratitude to Mo for assisting with the initial typing. Jack describes that he wrote the original first edition during a seven year period from the late 1970s to the early 1980s using Paper Clip – an early word processor that ran on a Commodore computer. He reviewed and edited it by printing to a dot-matrix printer. When it was complete, he sent the digital files to a company that specialized in printing self-published books. The original (and, as of this writing, only!) printing run consisted of fewer than 20 copies.

All of that took place before the venerable PC became ubiquitous, and well before Microsoft Windows was commonly available, with applications such as Microsoft Word or other more sophisticated word-processing programs. Fancy stylistic attributes such as multiple fonts, colors, and graphics were simply unavailable at that time. Even such seemingly simple things as changing from one type size to another were almost impossible given the technology of the time. The original manuscript files were stored in the proprietary Paper Clip format on a collection of single-sided, 8-inch floppy disks. Each floppy disk had sufficient capacity to hold only about 128,000 characters – typically one or two chapters of the book.

As Charlie and Martha began production of the digital second edition in the early Fall of 2014, we though it would be interesting to provide some insight into it preparation. In the late 1990s, shortly after Jack died, some who did not receive a copy of the first edition from the original print run expressed an interest in the book.

However, printing additional copies of the book was not feasible. It was prepared for distribution at a reunion of Jack’s children at National Harbor, in Oxen Hill, MD as the 20th anniversary of Kathleen Wright’s passing approached – 19 years since Jack himself left us.

Martha took on the task of trying to reconstruct a digital copy of the manuscript. Paper Clip was no longer available to read the original files. Moreover, due to technological advances, even finding a PC capable of reading the original 8-inch floppy disks was becoming more and more difficult. Luckily, Gary Toth, ever the tech guy, had inherited Jack’s original Commodore-64 and, when upgrading to a pre-Windows PC years later, had thought to transfer the files. In the absence of an 8-inch floppy disk, there was no simple, physical way to move them between incompatible machines. To accomplish that, a truly Rube Goldberg-esque lash-up was employed: the Commodore-64’s 300-baud modem was used to transmit the files one-by-one – each requiring an entire overnight period send the files from the Commodore-64 to the PC at that painfully slow rate.

Then came the task of transforming the recovered Paper Clip files into something understandable by one of the available word processing programs. Most of the text was salvaged, but none of the formatting of the original manuscript survived the transition. Everything had to be re-edited. In addition, some files were unreadable and several hundred pages of the original text were lost and had to be manually transcribed from the printed copies. Charlie and Martha collaborated in entering that text and editing those original recovered electronic files, eventually producing the digital second edition.

Having gone through all that trouble to recreate the book in digital form, we wanted to make sure that future generations would not have to repeat the ordeal of transcribing from one format to another. We had to decide on a file/format for the newly-recovered digital version. Using Microsoft Word (2010/2013 for both PC and Mac) we produced several different versions, each in a format common in 2014.

Comparing the second edition to the original 1985 printed first edition you will see that this is not a “warts-and-all” faithful reproduction. For the second edition we immediately dismissed the original dot-matrix Courier font in favor of a more readable one. We tried to capture all the italics, quotes, and other stylistic attributes of the original; though certainly more than a few were probably missed. Although we did correct a few spelling errors, add an occasional missing word, or remove a stray extra word here or there when mistakes were obvious; we have resisted the urge to make any intentional editorial changes to content. We have made no attempt to remove or reword odd or potentially offensive attempts at humor. This is, after all, Jack’s book. Also, although we did significant proof-reading, we did not go any extraordinary lengths to compare the text of the second edition to the original word-for-word.

We note that, while transcribing the missing portions, we did find that the digital files were not always identical to the printed version. In those cases, we ‘corrected’ the text you read here to match that of the printed first edition. We noted other occasional minor differences between the recovered files and the printed text and updated the text here to match the printed version. Clearly, Jack had done some last-minute editing before going to press and the recovered files did not reflect the ‘final’ version that he sent to press. Likely, we have missed other such small changes.

One of the resources we used, as we worked our way through this effort, was Jack’s personal copy of the book. As you might guess, that copy had numerous passages highlighted or underlined. In addition, we found notes written in the margins and newspaper clippings slipped in between the pages. To capture those additional thoughts for the digital editions, we added numerous Endnotes. Speaking of notes, while reading, you will occasionally encounter “asides” and parenthetical comments within the text, sometimes preceded by the notation “Editor’s Note.” Such comments reflect additions that Jack made during his final editing process. These are part of the original text – not something that we added.

Our biggest challenge, and the main impetus to undertaking this effort in the first place, was to assure a digital second edition in a format that would remain viable for some time into the future. We realized that it would be valuable to make sure that the digital product would be compatible with as many of the various contemporary reading options as possible – options that were not even envisioned, much less available, when the first edition was written – such as might be read directly on PCs, tablets, e-readers, smart-phones, and the like. In the end, we decided to produce multiple formats that would support browsers and eReaders available at the time.

One obvious difference in the digital editions relates to placement of the pictures. Time constraints prevented inclusion of the photos in the second edition before the 2014 reunion at National Harbor and so it does not include any of the pictures from the printed first edition. The third edition corrected that flaw. For the third edition version, we chose to integrate the photos with the text, for a better reader experience. Placement of the photos within the text of the third edition is almost entirely the result of our sometimes arbitrary decisions and we accept all blame for any perceived misplacement. When original photos were found, they were used – some are even in color! And Charlie took the liberty of adding a few new pictures. Sadly, though, most of the original photos and artwork were lost and had to be scanned from the printed original book. We spent considerable time attempting to touch up or otherwie improve the poor-quality of these reproductions as best we could. Still, some images remain quite small and details may be difficult for a reader to discern – especially in images which were re-sized, Xeroxed copies of newspaper and magazine articles and other printed documents. The text of such images is provided in Endnotes so that readers can actually have the benefit of reading the text of such pictures.

We hope you enjoy the result!

Martha and Charlie

Spring 2021

FOREWORD

I was at once amused and touched when my daughter KT first suggested, and Sr. Kathleen endorsed the idea, that I write my autobiography. I couldn’t imagine anyone profiting from the recitation of such a dull and ordinary tale. It is still probable that my work will be little read and even less enjoyed, but there is no longer any doubt in my mind as to why the construction of my life’s story has been a very good thing. Perhaps English historian William Stubbs sums up my main discovery best: “If a man wishes to learn something of a subject, his best policy is to write a book upon it.” While it has long been my practice to write analyses of troubling issues, the steady evolution of self-knowledge that came with the development of this autobiography was a continuing series of shocks and surprises. My experience only verifies Dr. Johnson’s observation to the effect that every man’s life is best written by himself (although he then went on to concede that his opportunities to know it were more than compensated for by his temptations to disguise it.) Perhaps the best reason why one should write his own life story is that advanced by historian Joseph Renana: One should only write about what one loves. This, then, has at worst been a labor of love and enlightenment for the author. One can only hope that it can be as much to at least a few readers.

But the project has, indeed, been labor. Apart from the shock of really confronting myself for the first time, my second biggest discovery has been that the writing of autobiography has to be the most difficult type of writing in the world. Whereas Carlyle has remarked that a well-written one is much rarer, and proceeds to convict Carlyle of being “as much an optimist in his criticism as he was a pessimist in his ethics.” Indeed, the seeker of truth in autobiography will eventually become a devout convert to pessimism. There are many reasons for this. First of all, one is overcome by the astonishing number and length of blank periods in one’s life. This frustration is particularly acute as regards one’s first decade on earth. This unhappy situation has prompted at least one wag to suggest that all biographies should start with Chapter Two. Kipling has underscored the vital importance of this blank period with his challenge to “Give me the first six years of a child’s life; and you can have the rest.” Yet, as Andre Maurois has noted, he could recall only a few outstanding memories up to the age of seven or eight. He has remarked that they appeared as tiny, isolated pictures surrounded on both sides by dark strands of forgetfulness, and he went on to state that, “This is not enough to explain the complex individuality which we all acquire by the age of six or seven.” If Kipling is right, and my reflection strongly suggests that he is, then the most careful dredging of the subconscious for even the seeming trivia of these highly formative years appears to be fully warranted.

There are other very real constraints operating against truth in autobiography. In the first place, hardly anyone has any real enthusiasm for confessing personal stupidity, much less personal shame. On the other hand, few would have the temerity to assume any vested right to violate the reputation or peace of mind of any figure peripheral to the story. English writer Philip Guedalla says that autobiography is an unrivaled vehicle for telling the truth about other people. Death Valley Scotty’s credo seems most apt: “Don’t say nothing that will hurt anybody.” Yet, we are surely shaped in some considerable measure by both the positive and the negative influences of those who share our environment. How can our hero realistically project the full story of his development without at some point incidentally incriminating some of the supporting players? An extremely fine sense of discretion is needed in such instances, for no one has the right to tell the whole truth (as they admittedly see it imperfectly) about others. Nevertheless, one must recognize that such discretion in fact operates as a distorting filter even under the best circumstances.

Nor is this the end of the problems with autobiography – other more subtle constraints yet remain. Maurois has contended on the one hand that autobiography is obliged to omit the many commonplaces of daily life to concentrate on the salient events, actions, and traits, but he has also conceded that in so doing one creates the impression that our hero’s life was one smooth tapestry of main events, whereas the great bulk of the unrecorded hours were much as dull as our own. On the other hand, Sir Walter Raleigh in effect goes even further, suggesting that accidents which may seem little more than trifles often develop qualities every bit as much as participation in great worldly events. As for these so-called great events, their recounting likewise entails peril. English philosopher Henry Spencer has observed that to omit incidents that mark the progress of our hero’s development and success diminishes the value of the narrative, but to the extent that such reflect any honor on him, their mere mention often translates into charges of vanity. Maurois extends the figure by noting that memory rationalizes; ascribing lofty motives for actions performed unwittingly or unconsciously. Clearly, pursuit of truth in autobiography is as vain and illusive as pursuit of a will-o’-the-wisp.

We must conclude with Maurois that the severest autobiography remains a piece of special pleading, and that when we attempt our own portrait for other people, we should not be surprised if the portrait is not accepted as a likeness. As Spencer has said, “An autobiography is a medium which produces some irremediable distortion.” Will Rogers has reinforced this with his wry observation to the effect that when you put down the good stuff that you should have done, and you leave out the bad stuff that you did do, well, that’s memoirs. As several wags have noted, “Autobiography is now as common as adultery, and hardly less reprehensible.” All the foregoing, of course, is merely to forge the proper perspective with regard to all that follows, and incidentally to explain the newly compounded word in our subtitle. As for the perspective, we yield to Isadora Duncan: “How can we write the truth about ourselves? Do we even know it? There is the vision our friends have of us; and the vision we have of ourselves; the vision our lover has of us, the vision our enemies have of us – all of these visions are different.”

As for titles, we found that all the good ones have already been used. We liked the casualness of Graham Greene’s A Sort of Life, and we cherished Oscar Levant’s A Smattering of Ignorance as even more apt. Something of Myself For My Friends Known and Unknown seemed just perfect. Too bad Kipling disposed of that one. And, had we wished to be more profound, we might have opted for By Any Name; the same being excerpted from American humorist Donald Robert Perry Marquis’s awesome declaration, “All religions, all life, all art, all expressions come down to this: to the effort of the human soul to break through its barrier of loneliness, of intolerable loneliness, and make contact with another seeking soul, or with what all souls seek, which is (by any name) God!” We finally settled upon the one we selected because it seemed at once both so historically right, and (please be kind) so characteristically Wright. You’ll find no apology here, either, for the quagmire of quotes. They are not, as one might reasonably suspect, an accidental betrayal of pseudo-intellectualism. Rather, they are willfully incorporated as insurance against the customary cliché, “Well, it was all very interesting, but I didn’t learn anything new.” With this single disavowal on record, then, and with due acknowledgment to Samuel Eliot Morison (for Volume Three of his Oxford History of the American People) and even more so to William Manchester (for his The Glory and the Dream), whose superb historical narratives contributed mightily to my ability to recreate and chronologically structure personal reflections and experiences in relation to the appropriately contemporary atmospherics and events, we are now ready to proceed. No one can plead that they haven’t been forewarned.

Jack Wright

Silver Spring, Maryland

16 Mar 1985

The best brought-up children are those who have seen their parents as they are. Hypocrisy is not the parent’s first duty. – G. B. Shaw

The central basis for all the major decisions of my life has been flight from my mother. Despite the carefully cultivated and quite public image to the contrary, she simply was not an easy person to love. She always seemed to keep you at arm’s length, and certainly she was the world’s champion faultfinder. Like a teacher, she assumed as a divine mission a constant right and responsibility to correct anyone, anywhere, anytime. Nothing, but nothing, ever suited her. It’s already almost a family joke – “Mother will surely make it to heaven, but she’s not going to like it there!”

She didn’t just keep house. And she certainly didn’t provide a home in which you could relax. What she did was maintain a showcase, always ready to receive visitors who rarely came. I firmly believe that it had to be her who coined the phrase, Everything has a place: everything in its place. No one in the family ever enjoyed our so-called living room. Except for the occasional welcoming of a relative, our living room was out-of-bounds. Smoking wasn’t then the rage it was later to become, but, if mother had allowed smoking at all, she would have been constantly on the move dumping and washing each ash tray after each flick of a cigarette. She could spy a piece of lint on a rug at 30 paces, maybe 50. Too bad they never gave prizes for museum-like living rooms as they sometimes do for outside gardens.

And there were never any halfway measures. Mother never got merely sick. She always got deathly sick. She never had a simple ache or pain. It was always an excruciating pain. She never felt just slightly warm or chilly. She was either dying of the heat or freezing to death. Amazing as it may seem, I never recognized what was wrong until very recently, in the course of enjoying one of John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee adventure novels. I can’t do better in describing mother than by quoting MacDonald directly:

Some of the classic symptoms of anxiety neurosis: the numbness, vivid and ugly dreams of something wrong with your body, diarrhea, depression, self-contempt. There are others: double vision, incontinence, and being always too hot or too cold, night sweats … an only child. A lot of pressure on you to be the best child ever. Impossible goal, of course. Sense of failure at not making it. So your mother died at peak vulnerability, and then your father died, and you never had a chance to prove to them you could hack it in the world… So, out of a sense of being terribly alone, you marry a very large and sort of limited guy. And it was the pursuit of perfection. You had all the images and symbols working for you.

That’s mother to a tee! She made a career of illness, real and imaginary, but always exaggerated. And while she wasn’t an only child, her mother died when she was sixteen, and her father when she was twenty. So, indeed, she never did have a chance to prove herself, and the scarred sense of self-worth (or, better said, “unworth”) endured almost to the day of her death. Not only did she lose both parents before making it in the world, the entire balance of her immediate family was wiped out by tuberculosis in the space of a mere dozen years; the four brothers before she was twenty-two, her only sister before she was twenty-seven. None of her siblings saw their thirtieth birthday.

All of this certainly had to be traumatic, and it apparently devastated mother. She must have felt incredibly alone – utterly abandoned and at peak vulnerability, since in those days young women were even more discriminated against than they are today. True, she in no sense married a very limited guy, but subsequently clear incompatibilities suggest that her marriage to a young college professor was a precipitate flight from insecurity into a cozy cultural realm which, like that of naval officers, confers certain inherent trappings of prestige and more-than-average respectability. You have all the images and symbols working for you. And the latter is what mother seemingly lived by. With her the important thing was always, “What will people think?” and “But people will see you.” Appearance was everything. Too bad she could never undergo the third degree of the Knights of Columbus.

I have no recollection of mother ever having volunteered a single positive remark about anything or anybody. When she beheld a rose, she saw only the thorns. If there be such awards, she fully merits exclusive rights to the title of Miss Pessimist of the years 1888 through 1981. Little wonder that I’ve always felt ambivalent about Mother’s Day. I just never could understand what all the shouting was about. My main impulse about mother was to run – to run away, far and fast. This was an impulse not shared by either my lone sister, Margaret, or by my lone brother, Tom, at least until many, many years later. Margaret was three years older than I, and Tom was four and one-half years younger than I. From the very outset my mother made it very clear that I enjoyed a much less favorable position than either my sister or my brother.

With sister, Margaret

First of all, my sister Margaret, being the eldest, naturally inherited the alter-parent role and authority whenever both my mother and father were away from home. My earliest and dominant recollection of sister Margaret was as an enemy; one who would never hesitate to do me in, and who in fact seemed to relish the accolades she inevitably received for reporting some minor (but admittedly willful) infraction on my part while the folks were out. More often than not she baited me into the indiscretion with the admonition, “You’d better not do so-and-so, or I’ll tell mother when she gets home.” And I would, and she would, then I’d bask in reflected glory as my mother would despairingly intone, “He must be possessed by the devil.” But what red-blooded American boy could ever resist a challenge like that? I’m certain that one of my early delights was driving my officious little proxy-parent sister up the wall.

My brother, on the other hand, had the wisdom and foresight to suffer an attack of rheumatic fever at about the age of five or six. I remember that it delayed his completion of the first grade (which he ended up skipping) for a year. More than that, it established him for life – though he soon completely recovered – as Poor Tom! (It amuses me that, to this day, even his wife refers to him as Poor Tom.) I must have been in the late teens before it dawned on me that, like damn Yankees, his appellation of Poor Tom wasn’t in fact a single word and his real name. This isn’t to suggest that he either ever precipitated or demanded the deference with which mother insisted that we treat him, but he sure as hell enjoyed it. He couldn’t have had a more protected and favored childhood had he been the only offspring of the Godfather and had twenty-four-hour Mafia guards. As for me, woe unto me if I so much as harmed a single hair of his head. So it was that I grew into first feeling like I was somewhere between a rock and a hard place – an unread book between two eye-catching book-ends.

Wright tribe on sister Margaret’s graduation

My father, as nearly as I can recall, always tried (and generally succeeded) in being extremely fair. Like St. Joseph, he was a just man. The trouble was, his intelligence apparatus, as far as I could see, was no better than our fumble-bumble CIA’s. Too often he was forced to act on what I, at least, thought was bad, biased, or incomplete information. I can’t fault him, though, for not just trying to get the facts, sir, like detective Joe Friday. Neither do I accuse the siblings of willful distortion or worse. It was sort of like how no two eye-witnesses ever seem to see things exactly the same, and I confess that early on I began to view things through a mental prism that filtered everything coming my way as just another manifestation of the let’s-sock-it-to-Jack syndrome. It just seemed to be a generally shared axiom, possibly a corollary of Murphy’s Law, that if anything went wrong, well, everybody just knew that I had caused it. Thus spurred on, I no doubt tried mightily to fulfill expectations, lest anyone feel cheated.

Like my mother, my father was also a native Washingtonian, as am I. And, in contrast to my mother’s parents, both of my father’s parents lived into their middle eighties. His father, like my mother’s father, was what would probably be termed a middle-level civil servant in the federal government. Grandpa Blakeney was a clerk in the Auditor’s Office of the Treasury Department. Grandpa Wright was the same in the Finance Branch of the War Department. So, the immediate roots, at least in terms of worldly professionalism, were not especially distinguished. We would probably call both families lower-middle-class today. My father was one of two boys, and he had six sisters. I am surprised as I try to write this how little I know about my father’s siblings. Two of the sisters had died before I was a year old. Two of the others, Edna and Alma, were married, and between them they had five sons. Of the other two, Edith ultimately retired from the government, where she worked for something like the Department of Education. The other, Sue, I only remember as a life-long cripple from arthritis. All lived to advanced years. My father’s only and younger brother Eliot, also married, and is probably best recognized by some of my children in conjunction with his wife, Aunt Agnes, now widowed in Ormond Beach, Florida. We will meet them again in the course of this story.

Early Pop

Naturally I can disclose many more particulars about my father than about any other member of his family. In addition to personal recollections, I have the benefit of a brief formal biography1 of him. It is part of a dissertation prepared in 1955 by Ann Martha Sandberg of the Catholic University. She subtitles this biography “Advocate of Peace,” and in it she describes him as having “a dynamic personality, vivid imagination, keen intellect, tireless energy, and a cultured mind.” He was all of this, plus, from my point of view at least, he was a good father and an exceedingly patient and thoughtful husband. He graduated from Georgetown University in 1911 and added his master’s and doctorate degrees at Catholic University in 1912 and 1916. He could boast a reading knowledge of German, French, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese – most probably as a by-product of his great facility in Latin, in which he was an instructor at Catholic University from 1911 to 1918. It was in pursuing his study of Latin that he virtually fell into his ultimate field of International Law and Political Science. This all came about through his doing his master’s thesis on St. Augustine’s idea of peace, and his subsequent critical analysis of Franciscus de Victoria’s treatise on the so-called just war, for his advanced degree, a Doctorate in Philosophy. (I deeply regret that I never got to ask my father the precise origin of the topics for these two dissertations, since they were so evidently critical and seemingly providential in directing the eventual course of his highly successful professional life.)

The latter critique literally launched his career as an expert in International Law, eliciting an invitation to join a branch of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to assist in the translation of Classics of International Law. He progressed from this position in 1923 to assume the chair of Political Science in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University where he served until 1930. While in the latter billet, Pop (which is what we always called him) made his first European visitation in 1926 as part of the Carnegie Endowment contingent of fifty professors who were reviewing the operations of various international organizations first-hand. Concurrently, he was the managing editor of the Constitutional Review of the State Department for several years. In 1919 he became a special advisor in historical research for the State Department in Latin American Affairs. Subsequently, the State Department assigned him to edit some international conferences in 1929–1930, this stint entailing four months’ service in the American Delegation to the London Naval Conference in 1930.

Also, in 1930, Pop received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law from Providence College in Rhode Island, and received the Papal Cross Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice from Pius XII for his Vice-Chairmanship of the Catholic University’s Golden Jubilee celebration. He had, on his return from London in 1930, joined the Catholic University as Professor of International Law and Head of the Department of Political Science, which post he still held at the time of his sudden death (of a heart attack) in 1945. Concurrently with this assignment he lectured for several semesters on International Law, American diplomacy, and Latin and Far Eastern affairs at the Postgraduate School of the U.S. Naval Academy and at the Turner Diplomatic School. Concurrently with all the foregoing, he authored more than two hundred publications pertaining to International Law and Political Science over the period extending from 1912 to his death in 1945, the same culminating with his comparative study of The Dumbarton Oak Proposals and the Covenant of the League of Nations which was published as a government document by Congressional Order, for use of the United Nations Conference at San Francisco beginning on 25 April 1945, and which resulted in the United Nations organization.

Such is Pop’s curriculum vitae – impressive, but not really revelatory of the man, or better the gentleman, for that is what he was, in the fullest sense of the word. He was courteous, forthright, compassionate, exceedingly patient, and quietly courageous. Also, he was ever a cheerful companion, a fascinating conversationalist never at a loss for just the right anecdote with which to underscore a point. He was also a devout optimist and a perpetual student. I don’t ever recall him relaxing without pen or book in hand. It’s not at all surprising that two of his best friends comment upon his reading habits. “We read a great deal,” volunteered his life-long boyhood chum, Fr. Quitman Beckley, O.P. “He was always reading learned books,” is how another old friend, historian Charles Tansil, underscored the matter. And he didn’t just read them. He absorbed them.

I suppose the dichotomy of affection in my mind for my mother and father is already abundantly evident, and I can only add, well, this is the way it was as I emerged into awareness and then grew into young manhood. Pop was friend; Mom was foe. And my brother and sister registered pretty much as self-seeking neutrals with Pop, and as allies of Mom. Rightly or wrongly, I saw things from the very beginning as being me against the world, with Pop as my only hope and refuge, but as a strict dispenser of justice. Mercy was still just an unknown x in the equation of my young life. One can do no more, especially this belatedly, than record one’s best impressions.

Having said all this, some attempt must yet be made, I suppose, to elaborate those specific qualities in my father’s overall character to which I may have fallen heir to varying degrees. Even as it was in the case of my mother, it remains for another to best delineate the unique character of my father. Let us defer to Catherine Drinker Bowen:

The professor is deliberate, he dislikes snap judgments, clever retorts at the expense of sincerity. There is a primal delightful innocence in him; he tells a funny story with all the gusto of Adam telling it for the first time to Eve. And he is tough fibered in his profession: a scorching review of his latest book is published in the historical quarterly [she happened to be writing of a history professor], and next Christmas holiday the author sits with the reviewer at the historians’ convention, companionably drinking beer in the hotel bar. The professors laugh at themselves, they laugh at life; they long ago abjured the bitch-goddess SUCCESS, and the best of them will fight for his scholastic ideals with a courage and persistence that would shame a soldier. The professor is not afraid of words like truth; in fact he is not afraid of words at all. Like the lawyer he loves to talk and teach, likes to exercise his mind and know he does it well. But unlike the lawyer, the professor has a wonderful confidence, somehow, that there is time to talk.

Well, I certainly can’t add a thing to that. That’s my Pop! But one final word anent both parents by yet another author strikes me as most relevant. He is speaking of his own derivative character in terms of his father as a teacher. Now, whereas my mother’s claim to being a teacher arises solely from the fact of her motherhood, she was by all accounts an indefatigable teacher, every bit as much as my father was a professional one. I therefore feel the following words of Andre Maurois are most apt with respect to my legacy from both of my parents:

My father passed all of his life in teaching… No one will deny that I am much given to criticism. Along with the exposition of my own views there has always gone a pointing out of the defects in the views of others… The tendency of fault-finding is dominant – disagreeably dominant. The indication of errors in thought and in speech made by those around, has all through life been an incurable habit – a habit for which I have often reproached myself, but to no purpose. Whence this habit?… (Again), while one half of a teacher’s time is spent in exposition, the other half is spent in criticism in detecting mistakes made by those saying their lessons, or in correcting exercises, or in checking calculations; and the implied powers, moral and intellectual, are used with a sense of a duty performed. And here let me add that in me, too, a sense of duty prompts criticism; for when, occasionally, I succeed in restraining myself from making a comment on something wrongfully said or executed, I have a feeling of discomfort, as though I’d left undone something which should have been done: the inherited tendency is on the way to become an instinct acting automatically.

There you have it – like father and mother: like son! I wonder … would any of my children dispute this? So, my origins lie with my parents to a considerably more than merely physical degree. But it would be wrong, I think, to leave it at that. They, too, had their origins, and before proceeding further, it might be well to digress briefly and place in the record (and this may be the last opportunity to pass the torch in this respect) what little I have been able to reconstruct about my parents’ forebears. As it was in the case of Mom and Pop, more biographical data are readily available about my father’s family than about my mother’s. One reason for this is, as already noted, my father enjoyed a relatively distinguished semi-public professional life. Another is that my mother was the sole living member of her immediate family for the last sixty-six years of her life, ending in December of 1981. Unfortunately, too, I didn’t personally try to pick Mom’s brains for family memories until she was already going on ninety and her recollection was already beginning to cloud over. This sad state of affairs makes it all the more imperative that I now set down the full extent of what I know.

My mother’s maiden name was Blakeney, that being an English family that had its origin in a town of that name on the northeast coast of the North Sea, barely 100 miles north of London in Norfolk County. It wasn’t until the summer of 1981, three years after I began this project, that I discovered that the Blakeney name is more or less irrelevant to our ancestry. It seems that Grandpa Blakeney’s original father died, and his widowed mother remarried a Blakeney who then formally adopted him. Actually, Grandpa Blakeney, though born in Sheffield, County York, England, was born of Irish parents with the name of KELLY! So it is that our progeny are effectively one-quarter Irish, and only barely (by an additional 1-1/4 sixteenths) more English. Another quarter of our children’s ancestry is Bohemian, with the balance being Scottish and German with a trace of Spanish. (Bohemian, of course, is the classification of individualists noted for their disaffection with conventional societal manners and mores, and it would seem that certain of our daughters exhibit this traditional ancestral disposition.)

In all events, Grandpa KELLY arrived alone in New York circa 1865 at the age of eighteen, and there became a schoolteacher. (Notice has already been given of my contention that a teacher’s correction complex has seemingly been inherited by me from my mother as well as my father. Perhaps my mother’s father was the source of mother’s teaching proclivity!) Anyhow, he soon gravitated, at the instigation of a friend who had preceded him from England, to the Soddy-Cleveland-Ducktown area of Tennessee (just east of Chattanooga and just north of the state line from Atlanta, Georgia), where he served as tutor to the family of a former English Lord. Soon thereafter, on 1 September 1867, he unaccountably enlisted as a Private in the U.S. Army at Memphis, Tennessee, under the alias of Thomas M. Nugent! (One can only conjecture that his flight from England and disguised entry into the Army were attempts to escape his mother and new stepfather, as he was still under 21 years of age.)

Although his Army commitment was for three years, Grandpa Kelly-Blakeney-Nugent was medically discharged after only 21 months. First of all, he had spent most of his enlistment in base hospitals due to intermittent fever and chronic diarrhea contracted early on in a swamp area camp near Wolf Creek on the outskirts of Memphis. This unproductive situation was further complicated by an improperly healed radius of his right forearm, which was broken in an accidental fall down barracks steps in a troop rumble to roll call. This resulted in his being declared 3/4’s unfit for manual labor, and so he was discharged on 1 May 1869 at Atlanta, Georgia. In due course Grandpa filed for and got a $4/month pension, and it was this latter record which enabled this tracing of his abortive military record. Following this military stint he returned to the Tennessee area where, at age 28 in 1875, he married 15-year-old Martha Elizabeth Austin of Alabama.

My mother’s mother was said to have been born on a plantation in Alabama, and her maternal grandmother’s name is said to have been Forester. It seems that Mr. Forester was killed in a Civil War battle near Nashville in the first six months of the war, and the family soon lost track of his estate, which is said to have been considerable. Also, mother’s grandmother soon after ended up, with one remaining loyal female slave, operating a boardinghouse in Ducktown. Presumably, this is where my maternal grandparents met. Following their marriage on 20 January 1875, Martha bore four sons before the family removed to Washington in 1885 to enable Grandpa to take up a federal government job. My mother and her only sister, Marie, were then born in Washington. Mother was baptized Anna Frances Susan and opted for the single middle name of Cecilia at confirmation.

The Blakeney family, with the exception of my mother, was decimated between 1902 and 1915, largely by tuberculosis, the last to go being my mother’s younger sister, Marie, who died at the age of 24. With my mother, she was a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office. My mother’s four brothers died within the eight-year span of 1902 and 1910. All died in their twenties. The oldest, Will, was an aide to Admiral George Dewey, who had been with Farragut at Mobile Bay and who subdued the Spanish at Manila Bay in 1898, but who was then serving (1902-1906) as President of the Navy’s General Board. Will was being groomed as naval attaché to Russia when he died. The second brother was John, also a Navy man. He is said to have made every major port in the world2 before he died at age 23. It is also said that he achieved at least a try-out with the old Washington baseball Senators.

I’ve been unable to unearth anything about the third brother, Charles, except that he worked for the Weather Bureau. As for the youngest brother, Al, he too was a Navy man at least briefly. He joined up by lying about his age at 16. His mother quickly intercepted him at Norfolk where she engineered his release by proving him underage. He ended up working for the Navy Department in Philadelphia, where it is also said that Grandpa Blakeney’s only known relative, a sister, lived. All we know about her is that she was married to a plumber who had a fetish for gold-plated water fittings throughout their house. But the only really curious disclosure in all of this, it seems to me, is that my maternal grandfather was another teacher, and that three of his sons were Navy-oriented. I had thought I was the first, and that I had established the family naval tradition in which my three living sons are already established. Not so. Fame is so fleeting!

With my father’s family the records are a little more complete, going back an additional generation on his father’s side and several more on his mother’s to an Edward Green who was born in 1740. The amazing aspect of this side of the family was that it was D.C.-Maryland centered for generations. In fact, my paternal grandfather was an officer in the Association of Oldest Inhabitants of D.C. My great-great-great-grandfather Green had a daughter Elizabeth who was married to a Mr. W. W. Dorney of Harford County, Maryland, by no less than Archbishop John Carroll, America’s first bishop and the founder of Georgetown University. Interestingly enough, Mr. Dorney’s parents were named John and Martha. The Dorneys had a daughter, Maria Agnes, who married Mr. Benjamin Thomas Watson of Prince Georges County, Maryland. They in turn had a daughter, Susannah Cecilia, who became my father’s mother. She was the youngest of nine in a family of seven girls and two boys. She married paternal grandfather, Johnson Eliot Wright, son of Benjamin C. Wright, who was born in Alexandria while it was still part of the District of Columbia.

At this point, a word is in order about one of my father’s mother’s sisters – my Great-Aunt Kate. She is particularly relevant to our story on two accounts. First of all, she bears the name of one of our daughters and one of our granddaughters. More than that, and to my total surprise, she has to be our family’s pioneer women’s libber. I remembered her only as an elderly recluse who always sat quietly rocking in her second-story room (which she never left) on Columbia Road, in northwest Washington. It was somewhat of a shock to discover, upon reading the age-84 memoirs (written in 1961) of the husband of one of my father’s sisters (a medical doctor in the Indian Service), that this reserved old lady had in her youth been the head teacher (yes, another one!) at a school for the Navajo Indians in New Mexico around the year 1900.

Not only that, she was the magnet who drew two of my father’s sisters for visits to that then-still-primitive area, one of whom – Edna, the wife-to-be of the doctor – would remain to raise a family. (My father’s sister Alma – another teacher – visited them sometime later.) Here was this young city girl, (my Aunt Edna) who had never mounted a horse before, suddenly full astride and slipping and sliding down tortuous mountain passes in darkness and in rain and after only the most elementary instruction: Sit straight up and let her have her head! Soon she was of necessity camping out, sleeping on the ground, and so fully integrated into the western outdoors life that she remained – you guessed it – to become the kindergarten teacher in her Aunt’s Indian school.

Her husband, the doctor and author of the aforesaid memoirs, rates a yet-to-be-written book in his own right – Frontier Doctor3. We can digress here only sufficiently to indicate that through him, his heroic wife, and my father’s Aunt Kate, your family had at least some part in the saga of how the West was won. He operated (and that is the proper word) from the general area of the Mesa Verde (SW corner of Colorado, NW corner of New Mexico) out of Fort Lewis (near Durango and north of the La Plata Mountains) to Fort Defiance (near Gallup). His father was the supervising engineer in the building of the railroad spur connecting Durango and Silverton. The good doctor’s practice, in the jargon of the Navy, covered everything from asshole to appetite. He removed cataracts, did amputations, pulled teeth, and performed chest, abdominal and every other kind of surgery. Having passed the state pharmacist exam while still in college, he also compounded his own prescriptions from raw chemicals.

Still not impressed? He delivered all four of his own children, and personally performed the autopsy on his only daughter, who died at age one month due to extensive stomach perforation caused by ingestion of a foreign body (a sliver of glass or razor blade). His second son, Frank, is named after my father (Herbert Francis Wright), as was our own Herbie. The good doctor spoke Navajo, and additionally administered to the Ute, and for two years to the Chiricahua Apache – of whom he states, While some were intelligent, many were ignorant, dirty drunkards. (The Navajo and Apache are linguistically connected, both being Athapascan.) The doctor died at age 92 in Carroll Manor in June of 1964.

Returning now to the thread of our story, my father’s father had a great uncle, Robert Wright, who was the Provost Marshal of Bladensburg during the Civil War. This, interestingly enough, is where my first grandson, another Robert Wright, was born. The first Robert inherited a gold watch as the eldest male survivor of another Wright, which was inscribed: “Prescribed to _____ Wright by General Lafayette, for taking care of him while he was wounded.” My father’s father had another great uncle, Judge James Wright, who was Chief Librarian of the Department of Justice. A few further tidbits include the fact that the equestrian statue of General Jackson in Lafayette Park was designed by a gentleman named Taylor, who happened to be the husband of grandfather Wright’s Aunt Martha. Another item, and one I personally remember, was that my grandfather used to be one of the surviving old-time volunteer firemen who used to pull the old pumping engine every Labor Day parade. He continued to do this until age 75, when the chore almost killed him even though they had youngsters helping on the lines.

I remember my paternal grandfather better than any other relative, I suppose, precisely because of the personal (if infrequent) interactions we shared. I recall his happily singing a popular song one day, Go Away, Old Man, Go Away, and I asked him how he could enjoy that song when he himself was an old man. Well, that earned me one big withering frown. I also remember the time he, my father and myself were checking out genealogy in old Alexandria graveyards one summer day. I was amazed when he harshly repelled an old beggar and said, “Get away from me, go get a job!” It was the first and probably only time I ever saw him exhibit the slightest discourtesy, and I was quite impressed. Finally, there was the time when I was a little older, and so was he. I tried to help him down the front porch stairs to the car when he was departing after a visit to our house. “Let go of my arm,” he said furiously, tearing himself out of my supporting grasp, “I’m not an old man yet.”

No doubt he was a very proud old gentleman, but if so, he was entitled. As one testimonial to him upon his retirement attests, he was “a Christian and a polished gentleman of the old school, very loyal, and an assiduous worker.” I can believe it! But he also had a delightful playful side. Being a Presbyterian, he’d surprise my grandmother by preparing Sunday breakfast while she was at mass. He’d bake new coins in the wheat muffins. Sometimes he even baked dollar bills into the muffins, having carefully inserted them into emptied walnut shells. And frequently, to the delight of his grandchildren, he’d exclaim, Grandma, I asked you to please fix that hole in my pocket, as he sent us scurrying to gather assorted coins that seemingly showered from the allegedly defective pocket. So much, then, for happy personal memories.

As for the other insights, they were largely garnered from my paternal Grandpa’s Reminiscences of an Octogenarian, which he compiled in the mid-1930s. Of these recollections (only lightly skimmed here) he wrote, “I write … in connection with my life to show what can be done in rearing a family of a wife and eight children, if one has the grit and determination. Never give up!” The latter, I’d say, is the predominant legacy I have derived from both of my parents and, apparently, their immediate ancestors. I only wish I might have personally known some of my mother’s family. Surely I would have understood her better. But, perhaps if her family had so endured, then she would never have so needed understanding!

One is never entirely without the instinct for looking around. – W. Whitman

I doubt if anyone who reads this will know that Nicholas Copernicus, the Polish founder of modern astronomy, died on March 24, 1543. I do, because I was born in Washington, D.C., exactly 375 years later. Financier Andrew Mellon, the late movie actor Steve McQueen, and former Governor of New York and two-time presidential candidate Thomas E. Dewey are among others who were likewise born on 24 March. To the rising chorus of “Who cares?” I can only say that I apparently do. I include this minutiae here precisely because it is so typical of the way my strange mind works. I’ve always had a weird interest in my birthday, especially as regards happenings on that date. Thus, on 24 March 1818 Henry Clay said, “All religions united with the government are more or less inimical to liberty. All separated from government, are compatible with liberty.” And on 24 March 1900, ground was broken for the first successful New York City subway. Perhaps more germane to my family history is that on 24 March 1882 Robert Koch announced discovery of the tubercle bacillus. This has a particular relevance to my life story, since it was this little bug that wiped out every last one of my mother’s relatives. So much, in general, for all you ever wanted to know about 24 March but were afraid to ask.

Now, how about that specific 24 March of 1918, a Palm Sunday? That was the day I was born. It was, according to the Washington Star of that date, a partly cloudy day, with a high of 55 and low of 44. Interestingly enough, the front page cartoon depicts Uncle Sam saying to a small boy standing in a junk-filled backyard, “Son, just see what you could do with that old backyard!” Uncle Sam was holding up a picture of a victory garden (and I got around to taking his advice exactly 60 years later!) Everything else on the first page of the newspaper concerned the war: World War I. One headline proclaimed: “Gunfire Is Veritable Hell; Explosions Are Continuous.” Other headlines were: “Battle Of Great Intensity Continues, Hague Flashes”; “Children Play Marseillaise As Hun Airmen Bomb Paris”; “Two District Men Interred,” (with instructions on “How To Address Mail For Prisoners In Germany”); and so on.

This was the famous (and last) big German spring offensive that smashed through Picardy (which is to the north of Paris and gave rise to the song Roses of Picardy). Another headline cautioned “Fate of Allies Now Depends Upon Number Of Positions – Must Break Weight Of First German Thrust.” This, then, was the world into which I was born a world in deadly turmoil. And the very fact of my birth at that particular time is what kept my father at home (being deferred as a multiple father, a service my spouse Kathleen likewise rendered for her father) thereby saving him from the rain of destruction and possible death in the fields of Picardy.

The main headline, however, which was splashed across the full width of the top of the front page of the Star in inch-high type on that fateful day, was: “GERMANS SLAUGHTERED IN ATTACK; SHELLS HURLED 74-1/2 MILES ON PARIS.” As the twin feature stories elaborated, the Kaiser’s forces had been pushed back on a 21-mile front to a depth of four to nine miles in a tremendous battle near St. Quentin as massed Teuton formations were cut to pieces. As for this advent of Big Bertha, the paper reported “American Army Officers Are Dumbfounded By Ordnance Feat.” (So, what’s new? At the height of WWII, FDR’s Chief of Staff Admiral William Leahy said of the Manhattan Project, “The bomb will never go off, and I speak as an expert in explosives.”) They theorized that perhaps the shells were being dropped by enemy planes, and that the rifling found on shell fragments (which would testify to their source being a gun) was merely a ruse to conceal the true source. Another theory was that some natives had turned traitor and had trained their own guns around to strike at Paris from much closer in than the forwardmost German position. In short, as is so often the case with the regimented mind, the military officials among the allies couldn’t accept the evidence before their eyes because they hadn’t invented it first. As for me, I think it only fitting that my birth into the world should be saluted by the largest gun ever known to civilization. And, with the advent of missiles, it is likely to remain the largest ever built.

So, let me tell you a little about this unique weapon, with the aid of S. L. A. Marshall’s excellent history, World War I. The gun (or guns, as it turned out to be a battery of three) first opened up on Paris from 75 miles out at 0720 on 23 March 1918, the news reaching America in time for the morning newspapers of the next day. They were the German Navy’s newest 15-inch, 45-caliber gun (that is, more than 56 feet long), with the tube rifled down to 8.26 inches, to impart a high spin rate around its longitudinal axis, thereby preventing tumbling and providing greater accuracy as well as range through the resulting gyroscopic action. The shells stood about waist high, but the powder bags which impelled them were twice as tall as a man. For firing, the piece was invariably pointed at an elevation of 50 degrees, with necessary range adjustments accomplished through increasing/decreasing the number of powder charges. The projectiles left the muzzle with a velocity of one mile per second, traveling 12 miles up into air so rare that it would perform according to the law first described by Galileo for maximum range in a vacuum – thereby serving as a sort of forerunner of the civilian-scaring V-2 rockets used against London in World War II.

The bombardment continued for a week, culminating in the tragedy of Good Friday, 29 March. The Church of St. Gervais, opposite the Hotel de Ville, was crowded with kneeling worshipers when at 1630 a projectile struck the roof. A stone pillar crumbled, and the stone vault that it supported cracked wide apart, dropping tons of rock on the congregation … (leaving) eighty-eight dead on the floor and sixty-eight desperately injured. But things weren’t going all that well with the huge guns; one having blown up killing five crewmen. Also, French railway artillery only seven miles from the front had homed-in on the Big Bertha site with 15-inch shells. Finally, the two remaining guns were soon worn out and had to be replaced, so that only intermittent firing continued to 1 May, when the guns were phased out altogether. Over this period the battery had fired some 200 rounds. It was not a significant factor in the war, and was more a technical advancement than a military success. The fear it engendered did impact civilian morale, however, and this continued to be a matter of some moment.

But all the foregoing was transpiring overseas, far, far away from me, and I was totally oblivious to it all and to virtually everything else. I suppose everyone at some point in their life tries mightily to recall and fix in time their very first recollection of awareness. As near as I can tell, my first memories derive from when I was about four years old. We lived on Oak St. N.W., just off 16th Street, in a row house. I remember that a family named Briggs lived next door on the right, and they had a boy perhaps a little bit older than I. His name was Leon, and I was not allowed to play with him, but I have no idea why. I vividly recall sneaking with him into his basement one day to see his toys. I was frightened to death that I would be caught and punished, but I wasn’t. I certainly knew I wasn’t supposed to be there, and so I was not only excited but fearful. On our left lived a family named Allen, and they had a much older daughter, Nina, possibly in her teens, who was stage-struck and who went on to become a singer/dancer in a traveling show group that featured Victor Herbert operettas such as Naughty Marietta, and Kiss Me Again. I remember her as being very pretty, with long curly hair, dark eyes with long lashes, and beautiful flashing white teeth.

Chocolate, Pop-like goatee

I recall I used to sit on a high stool on the back porch and operate a lever on the kitchen window shutter like it was the electrical controller I had apparently seen on the nearby 14th Street streetcars. I could play all day as a streetcar motorman and conductor, simulating the sound with a humming “nun-nun, nun-nun, nun-nun” (when the operating lever was in the “run” position, of course). I also emulated the “p-shish” of the air brake when the lever was in the stop position, and had a foot-operated “ding-ding” alarm to signal stop and go and to clear the track ahead. I was your complete motorman, and I never had an accident, but I finally had to give it up. This was when I saw Mrs. Allen and my mother laughing at me from the other side of the kitchen window one day. That, for me, ruined the whole deal. I never felt comfortable again as a streetcar operator. It is probably just as well, because years later street-cars were phased out and I would have been out of a job. (This sort of reminds me of how, in 1945, when all sailors were being released from the Navy, dozens of them would insist on working the last month in the barbershop aboard ship “We can always get a job cutting hair,” they’d explain. “There’ll always be a demand for barbers, just like undertakers.” I’ve often wondered since whatever happened to the poor slobs who had the misfortune of being discharged during the long-hair craze of the 1960s.)

Sailor and Horseman

Another example of my earliest awareness is that I recall sitting on the cedar chest at the front upstairs window one afternoon while my mother was feeding Poor Tom as she rocked in a chair behind me. Suddenly I spied my sister returning from school, walking with our cousin Eliot, who lived just two blocks further east on Oak St., across 14th St.. The trouble was, she was using a prohibited route that took her past a small delicatessen-type store on Center St., which angled into Oak St. from the south just a little bit east of our house. I remember the store as “Dwarn’s,” which may be nothing like its real name. For some reason unknown to me, she was not allowed to go near Dwarn’s. So, I did it, I squealed on her, and with much delight as I recall. “There goes Margaret with El,” I exclaimed, “And she’s going right by Dwarn’s!” This is the only time I can recall that I was the victor in such a situation. It was always, it seemed to me, the other way around. Who says revenge isn’t sweet? I didn’t go unpunished, however, although the two events are probably totally unrelated. I downed some canned peaches one night for dessert, and with unremitting vigor they came right back up. I didn’t eat canned peaches again until after I was married many years later. Divine revenge? “How inscrutable His judgments, how unsearchable His ways.” – Ro 11:33.

Already braced-up for USNA

I have only one recollection of my father in this early period when I was less than five years old. One morning he tied a cardboard box atop of a sled, put me and sister Margaret in it, and started pulling us through a big snow up 16th St. toward Park Rd., which was four blocks to the south. I remember he stopped there, in front of Sacred Heart Church, to talk to friends there. And he talked and he talked. What had started as a delightful surprise ride through the snow turned into a freezing disaster. We just sat there, getting more and more impatient to get going again. I don’t even remember starting up again. I don’t know if I blacked out with rage because someone had usurped this rare favor from Pop, or if we fainted from the cold.

This could have been in late January 1922, as the great Knickerbocker disaster occurred 28 January 1922, when I was almost four. This was the collapse of a theater roof on a full audience due to excessively heavy snow. Ninety-eight people died (and about 100 more were injured). and almost all were neighbors, since the Knickerbocker (the forerunner of the Ambassador) stood nearby at the corner of 17th St. and Columbia Road. As of the 1949 issuance of the Weather Bureau’s Climatic Handbook for Washington D.C., this was “the greatest snowstorm in the 75-year meteorological history of Washington,” and occurred over the period of 27–29 January 1922, just two months short of my fourth birthday. There were nine inches of snow on the ground at the end of the first day, and 28 inches at the end of the second day, with all streetcar service throughout the District having been abandoned by 7:00 PM that night. Final measurements in nearby areas ran as high as 36 inches. I’ve always hated snow, especially since having to pay for auto accidents, but maybe this all started then, that “Sad Day at Sacred Heart.”

The foregoing comprises the sum total of my recollections of first awareness. But there is a lot more I know about myself in those days, thanks largely to stories told to me by my mother (when I was already sixty and she was going on ninety, and her mind was naturally not quite as sharp as it once had been). The biggest thing to occur in my very young life was my very near death. This all happened on my second birthday, and naturally I have no personal recollection of it. Mother has told the story many times, and though precise numbers sometimes vary, the substance always comes out about the same. It all began around three o’clock in the afternoon of 24 March 1920. Suddenly, I went into convulsions without any warning. My Merck Manual defines convulsions as violent involuntary contractions or repeated contractions (a series of spasms) of the voluntary muscles. In any event, my mother was alone with me, except for my sister Margaret (who at age five was not much help). Though she could no longer lift me, as I was huge for my age, she somehow got me to the bathroom and submerged all but my face in very warm water. This stemmed the convulsion, but left me unconscious. She then called our family doctor, Dr. Cogswell, who said he’d be right over, but that it sounded very bad. She then called Pop, who immediately headed for home. During the next 24 hours I had four more convulsions, but now Pop was able to trundle me into the tub to arrest them. The doctor told Mom that she had done precisely the right thing, and that her correct and fast action had probably saved my life. “But,” he went on, “I don’t want to deceive you. This [I still remained unconscious] is very, very bad. In all likelihood he is going to die.”

The spasms came so suddenly and unexpectedly that they finally stopped even trying to clothe me, and merely re-wrapped me in a blanket after each attack. No one could come up with any explanation for it at all, no hint of a possible cause. I couldn’t be left alone for a minute. Mom and Pop took turns in being constantly at my side, night and day. They both spent their time on watch massaging my arms and legs to maintain circulation and soothe the violently reacting muscles. They not only got very little sleep, Mom recalls that some days they themselves even forgot to eat. Grandma Wright had at once taken Margaret to her home (at 14th St.. and Columbia Rd.) to help out, and Grandpa Wright was apt to drop in any time of the day or night. Mom recalls that he’d come in, go up to my bedroom, look me over for a minute and say, “Well, he doesn’t seem any worse, that’s good.” Then he’d leave. The doctor, too, would drop in anytime he was in the neighborhood, which was several times in the course of each 24 hours. Yes, Virginia, they made house calls in those days. (And if you understand that last line, then you’re over 40 years old at least.)

The convulsions ceased after the fifth one, but I still didn’t regain consciousness. The doctors had given up on me, saying there was nothing they could do, and that death was only a question of time. At that point a huge swelling developed in the left side of my throat. An eye-ear-nose-throat specialist was called in – the best in the city – a Dr. Warner. He took one look at me and announced that he’d have to operate then and there. Sheets were spread on a small desk-sized table (which I later used on Dallas Ave. as a workbench), and with Mom in attendance, he proceeded to lance my throat. Mom says that several cups of poisonous pus poured out. My sister embellishes this with her recollection that three doctors were in attendance for the operation: Dr. Warner, Dr. Cogswell, and a Dr. Holden, who turns out to be the father of the Dr. Raymond Holden who delivered every one of our children from Charlie through Herbie. Also my sister says there were three such operations over three succeeding days, and that every time she saw the three doctors come into the house, she immediately took off for the farthest corner of the backyard, because she couldn’t stand the screaming (while unconscious?) that always attended their presence.

Several weeks later (and Mom recalls that I was unconscious for between three and four weeks, and nearer to the latter), I suddenly woke up for the first time since it all began. Mom was rocking close by, and her first hint that I’d finally snapped out of it was when she heard me say, “I want an egg!” (How is that, Mary, for a testimonial for the United Egg Producers?) Anyhow, these operations left a rough two-inch scar on my left neck, just under the jaw hinge (Yes! I ultimately survived!), but it blends right into the creases of my neck so that it is rarely visible. Sometimes, whether due to my metabolism or the weather, I do not know, it becomes quite visible through assuming a different skin color than the surrounding area. But usually, no one even notices it. (As a matter of fact, I’d been undergoing so-called thorough physical examinations annually in the Navy for a half-dozen years before it was discovered and added to my health record charts as a “distinguishing mark.” It was discovered by an “old pro” doctor from Massachusetts General in Boston, who had been converted into a Lieutenant (junior grade) by the war. He asked me about it, and I started to tell all. He yelled, “That’s enough! The less anyone knows about that the better. You don’t want all that in your service record.” And then he wrote under “cause” the two words “childhood accident,” for reasons that will soon become clear.

Mom couldn’t believe her ears when she suddenly heard my voice for the first time in almost a month. But she gave me the egg since, she says, they had been unable to get anything into me over the past several weeks except for a little carefully administered liquids. This was before intravenous feeding, folks, and Mom says that at this point I looked like one of those starving kids they show on TV who are victims of the drought in Africa. In fact, all agreed that I had survived so long with so little sustenance precisely because I had been such a big and healthy specimen at the start. (The same claim was made regarding my son George after his near fatal flying accident in 1968. He had been working out daily, doing calisthenics and lots of running. The doctors said he would never had made it if he hadn’t started off in such superior condition. The also gave an assist to his parachute training at Fort Benning, suggesting that his reflexes had been pre-conditioned on how best to hit the ground and roll.) Anyhow, by the time I finished my egg, the doctor had happened to drop in, as he so frequently did (and Mom says his small bill was almost embarrassing), and he couldn’t believe his eyes. I asked for another egg, and Mom turned to the doctor to ask it if was okay. The doctor happily exclaimed, “Anything! Give him anything he wants.”

So I started to get well, although my sister remembers that I kept throwing up a lot, and both she and Mom confirm that I had to learn how to walk all over again. It was several months later, when things had finally calmed down and were almost back to normal, that Mom suddenly remembered something. One day, several weeks before my first convulsion, she had found me with a purple substance all over my face and inside my mouth. A search soon disclosed that I had apparently been sucking one of my father’s rubber stamp indelible ink pads. Poison! I’d found it in one of several as yet unpacked boxes of his gear, that remained from our February move to Oak St. She immediately swabbed and flushed both the outside and inside of my mouth with boric acid solution, thoroughly, and all seemed well. But evidently I had ingested quite a bit of the ink. All the doctors agreed that this is what undoubtedly caused my convulsions and the associated neck gland condition.

Now only one question remained – how did Mom know what to do for convulsions? It turns out that one of her investments upon getting married was a family home medical book. She figured it was part of her responsibility, as a wife and soon-to-be mother, to be prepared to deal with all types of sicknesses and health emergencies. So, she had read the whole book cover-to-cover several times. She absorbed it. In a word, she was “prepared.” So it was, on another occasion about this time, I fell over backward from my rocking chair and split my head open on our iron radiator (now you all know I do have a hole in my head). Mom coolly shaved off the surrounding hair, flushed it with boric acid, effectively sutured it with tape over a sterile pad, and left the doctor with nothing to do but add, “Perfectly done.” Now I ask you, children, does that sound familiar? And you thought I had invented planning. Not so. I apparently (and unconsciously) inherited this propensity from my mother early on, and we’ll hear more of this later.

The foregoing discovery, that I had an inherited tendency to look ahead and plan for every conceivable possibility, was one of many surprises that evolved in the course of developing this narrative. I’d reflect on a particular trait, and then I’d conclude that I’d gotten it from my engineering discipline as it matured in post-graduate school. Then I’d recall earlier indications of that trait which had occurred prior to post-graduate school. So, I’d walk it back and attribute it to the regimentation and scientific training at USNA. Later, another earlier indication would result in my ascribing it to the concentrated discipline inculcated at prep school. And so on, and so on. Invariably, exploring various traits, I’d trace them further and further back until there was only one possible source – early home life.